Hele Bed and Bamboo Stick: One Lever, Two Usages, Two Kinds of Noodles

The same lever is used in different geographical locations and societies in different ways, while such ways are constructed by different agricultural conditions, the extent of urbanization, and the development of commercial culture.

Written by Jack Linzhou Xing

Published on 27/12/2020

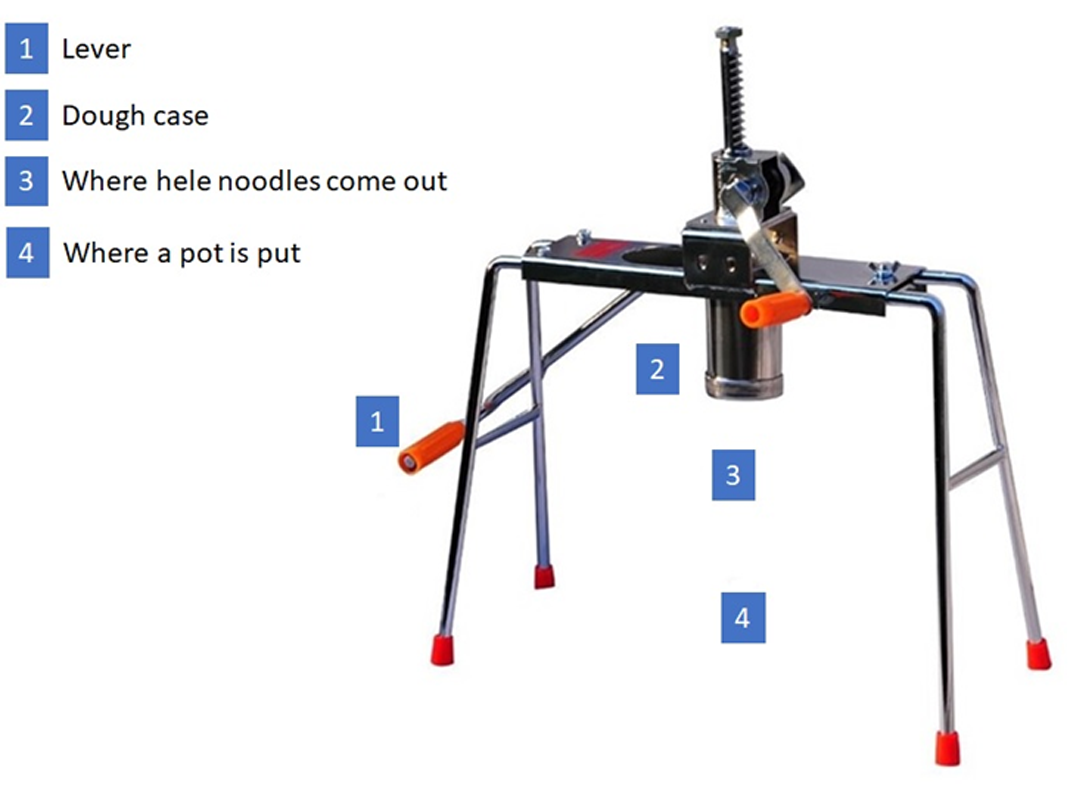

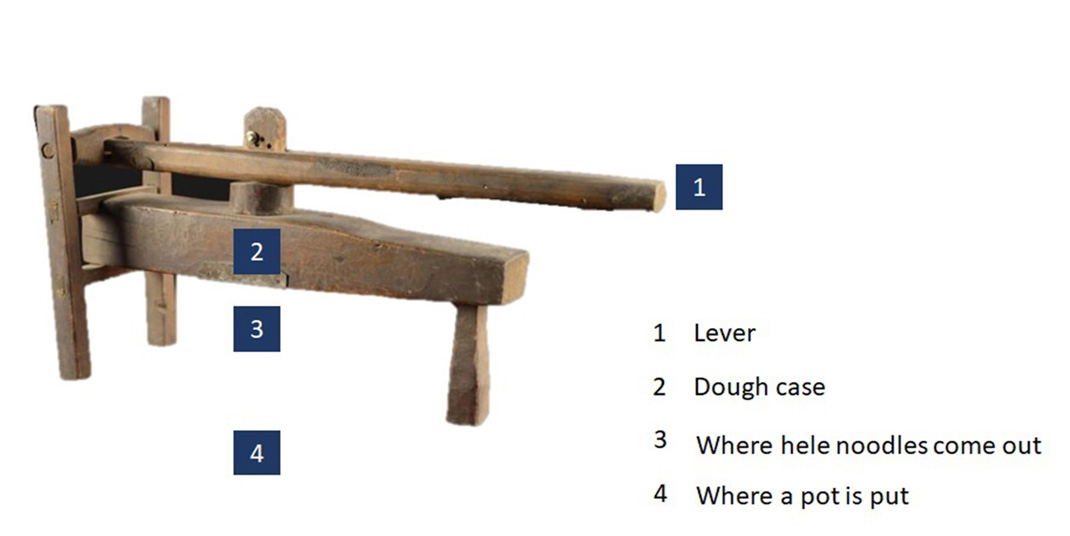

Figure 1 shows a typical cooking machine commonly found in families in Shanxi, Shaanxi, part of Henan, and part of Inner Mongolia, China. Its name is hele bed (hele chuang, 饸饹床), and, as the name suggests, is used for making hele noodles.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many schools conducted online teaching where students and teachers have class at home. In Figure 1, a teacher in Shanxi Province, Northern China, innovatively used the frame to fix her iPad, so that she could put the paper on the desk and under the camera of the iPad, write on the paper, and teach students how to solve math problems.

However, where can one find such a frame? It is a typical cooking machine commonly found in families in Shanxi, Shaanxi, part of Henan, and part of Inner Mongolia, China. Its name is hele bed (hele chuang, 饸饹床), and, as the name suggests, is used for making hele noodles.

Hele Bed: Mechanization against Large-scale Production

Despite the various noodle-making techniques across East Asia, there are three typical techniques in Northern China, among which hele is the one with the most “technological contents.” The most common technique, also used in making Japanese ramen and soba noodles, involves making a dough, roll it into a thin slice, and cutting it into strips. The second technique, represented by that of Lanzhou Beef Noodles, involves making dough and stretching it into noodle strips by hand. The third one, represented by that of Shanxi Sliced Noodles, involves making a dough, directly slicing on the top of the dough, and making flat noodle strips. Nowadays, all these techniques have been largely mechanized, but they can be achieved via hands and tools as simple as a rolling pin and a knife. In comparison, to make hele noodles, you must have a large frame that exploits the leverage principle.

Major components of a hele bed include the lever and the dough case. When making the noodles, you put the dough into the dough case, and press the lever so as to press the dough. At the bottom of the dough case is a sieve with holes. One hele bed usually pairs with sieves with different sizes of holes. When the dough was pressed, cylindrical noodle strips in the thickness corresponding to the size of the holes come out immediately. Eating fresh is largely emphasized in hele-making: The pot with boiled water is usually put under the hele bed. When the noodle strips come out, they go directly into the hot pot and get cooked.

Why do people bother making noodles with such a complicated machine? One of the major reasons lies in the origin and ingredients of hele noodles. Shanxi, Northern Shaanxi, and Inner Mongolia, where hele noodles originated from, were dominated by soil and climate conditions better for growing coarse grains such as soba, oatmeal, maize, and sweet potatoes. Compared to wheat, these grains generally contain less gluten and have a rougher and harder mouthfeel, making them less versatile than wheat and difficult to eat in diversified ways. To make these grains into noodles with a chewy and smooth mouthfeel, people dropped other typical noodle-making techniques. With the lever machine, hard dough in the abovementioned grains (usually mixed with some wheat) which are difficult to knead and stretch thoroughly can be directly processed into noodle strips. Provinces near Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Inner Mongolia, including part of Hebei and Henan, also adopted a similar food culture.

Different from other large-scale noodle-making machines typically seen in big restaurants and noodle-making factories and workshops, hele bed is usually used in families and small restaurants. Given that noodles coming out of hele beds are immediately cooked and served, in this case, automation led by the complicated machines does not necessarily lead to large-scale production and extreme convenience in selling or serving.

Bamboo Stick: The Lever to Facilitate Commercialization

Another noodle-making device exploiting the leverage principle, with a much simpler structure, is the bamboo sticks used in making bamboo noodles (or following the Cantonese pronunciation Jook-sing noodles竹升面) in southern China. Bamboo noodles is the major ingredient in the famous Cantonese-style wonton noodles, reputed for their nice, smooth, and chewy mouthfeel.

To achieve the abovementioned advantage, the dough of bamboo noodles is typically made of duck egg yolks rather than water. This makes it extremely difficult to be kneaded by hand. In this case, bamboo sticks serve as a huge rolling pin. One end of the stick is fixed on the wall. When making bamboo noodles, the maker puts the big doughs under the middle of the stick, while he or she rides on the other end of it. Then, by jumping up and down, the maker’s body puts the stick in motion and presses the doughs hundreds and thousands of times. Only after this process can the dough start to be pliable and obtain great mouthfeel. Afterwards, the flattened dough is put into noodle-making machines, and cut into thin noodle strips.

Besides the factor of mouthfeel, the necessity of bamboo sticks is led by another reason. Bamboo noodles were originally served as street food. Food sellers put the noodles, other ingredients, and a big pot in the food carts and went onto the street. To ensure freshness, only when customers were buying a bowl of noodles would the seller boil and cook the noodles from raw. Faced with the uncertainty of business, the warranty period becomes an important issue: delicious noodles should not only stay fresh within several days, but also stay chewy and pliable under long times of waiting, boiling, and soaking. This required raw noodle strips to be very dry and hard, and resulted in the method of making noodles with only egg yolks and pressing big doughs with bamboo sticks.

Such a process makes bamboo noodles more or less like instant noodles. Even though bamboo noodles nowadays are no longer sold in food carts, a similar style of serving and distribution persists. Given the inefficient and time-consuming nature of pressing small doughs with big bamboo sticks, the making of bamboo noodle strips was gradually separated from selling bamboo noodles in restaurants and became a specialized business: most bamboo noodle restaurants do not make their own noodle strips but buy noodle strips from specialized workshops.

One Leverage, Two Social Constructions

Compared to those of making hele noodles, the technique and device of making bamboo noodles similarly utilize the leverage principle. Nevertheless, the usages of the levers are different. In Northern Chinese provinces, levers are used to turn grains that are difficult to cook into noodles, while in Southern China, it is used for producing chewy and pliable noodles suitable for long-term storage. In the case of hele noodles, levers originally functioned to help agricultural households with difficulty to grow wheat to enjoy noodles, whereas, in the case of bamboo noodles, it enabled commercial selling of an urban food with a unique and outstanding mouthfeel. The same lever is used in different geographical locations and societies in different ways, while such ways are constructed by different agricultural conditions, the extent of urbanization, and development of commercial culture. Moreover, the different usages of levers lead to distinct business organization and trajectories of specialization: while hele bed is largely a domestic and smallrestaurant machine, the usage of bamboo sticks became a specialized step of largescale production of noodles.

With the higher level of automation and mechanization coming in, manpower hele beds became hydraulic pressure hele machines, while bamboo sticks are gradually substituted by automatic bamboo noodle-making machines. Nevertheless, given the different usages of levers, the destinies of people who conduct the noodle-making business are different. Hele noodles are still largely home-made with traditional hele beds; in small restaurants, hydraulic hele beds gradually become popular, while human cooks and restaurant runners still remain at work in charge of making doughs and cooking the soup base. In the case of bamboo noodles, noodle makers have been experiencing serious unemployment, partly because their jobs are such a specialized and vulnerable step along a highly commercialized “industrial chain” that can be easily substituted by the machine.