Menstrual Pads, Its History, and Its Cultural Meaning

Disposable menstrual pads became the mainstream in China in just 30 years, but some are struggling to get them in the country.

Written by Lok Hang Fung

Published on 03/05/2022

In early January, 2022, two years after the worldwide outbreak of COVID-19, an unexpected piece of news about the pandemic in mainland China went viral: a woman in Xi’an, at the time the epicentre of the pandemic and where strict lockdown had been imposed since 22 December, begged a COVID control worker for menstrual pads. In the video, the menstruating woman was tearfully telling the control worker that her Aunt Flow had arrived (大姨媽來了). When the control worker rather indifferently told her that no one could get out of the quarantine building and the only way was to ask someone to deliver the pads, the woman bursted out and cried “does that mean I need to bleed a river of blood?”

If this incident alone was shocking enough, it was not the end of the story. On 6th January, Chinese author Wu Kejing (吳克敬) published an article that bashed the woman saying that she was “pretentious”, “acting like a princess” and that she should know clearly “when her period was going to come”. Turned out he was the one who sparked fury as netizens criticised him as apathetic, backward and even misogynistic. How can someone who has not even menstruated once comment so callously and dismiss the urgent needs of the woman?

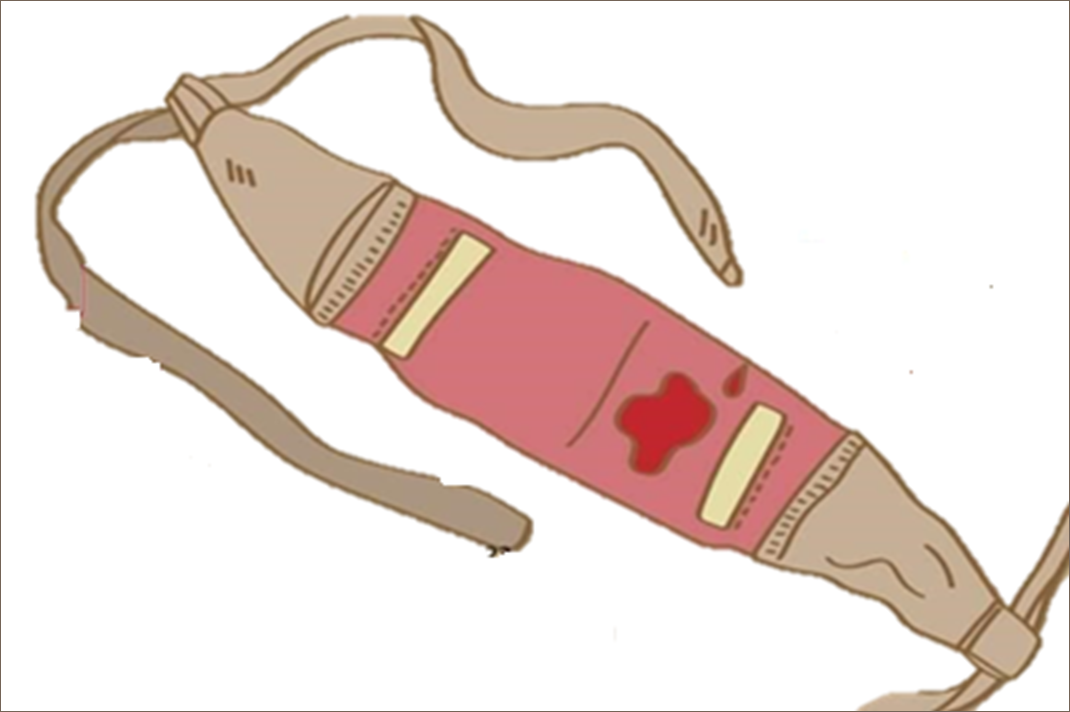

It was made clear that gender equality is still a long way to go and menstrual education in China is very lacking. But just a little more than a hundred years ago, it would have been really “princessy” to ask for menstrual pads in China when you are on period. Menstrual pads barely existed in China until the 1920s, and fact is that until the 1970s in Taiwan and mainland China, menstrual cloth (something like reusable cloth pads some of us use today; made from any cloth available, even old, worn clothes; washed and reused after use) and sanitary belts (月事帶; somewhat like T-Back panties where you attach non-adhesive pads or, more often, tissue paper, straw or even ashes) were the mainstream. How did menstrual pads become the taken-for-granted everyday product in China? How did menstrual pads, a Western invention, interact with Chinese medicine notions of biology and menstruation? Using menstrual pads as a vantage point, the intersection of patriarchy, biology and consumerism in China will be unfolded below.

The Modern Menstrual Pad – How it Started

Like many “non-innocent”[1] technoscience inventions rooted in militarism and/or colonialism, disposable menstrual pads that are used and purchased today is in fact a wartime legacy. Although the first-ever commercially sold menstrual pad, Johnson & Johnson’s Lister’s Towel did not directly have something to do with war, the first widely sold menstrual pad did. It was Kotex (yes, the same Kotex a lot of us use today) launched by Kimberly-Clark in 1920. In a 1921 Kotex advertisement, the company wrote the story themselves: American nurses in France used cellucotton (wood pulp fibre), which was sold by the company as bandages for absorbing blood in wounds during the First World War, as “bandages” for their private parts.[2] The company saw business potential and needed a way to use up leftover cellucotton, and later on developed Kotex (“cotton-like texture”), the world’s first commercially available disposable menstrual pad that was actually cheap enough to be disposed of after use.

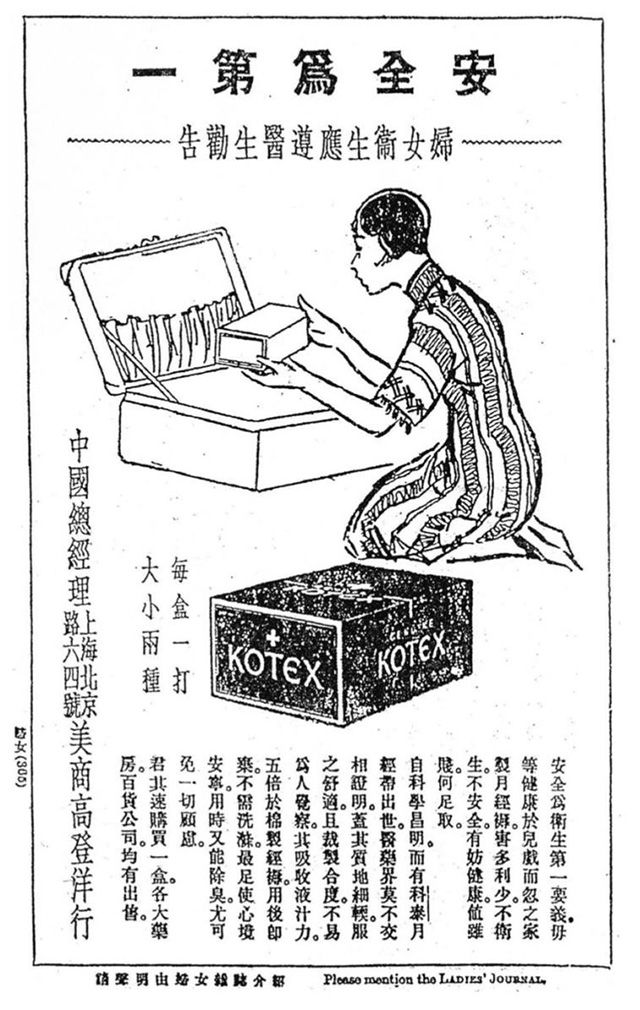

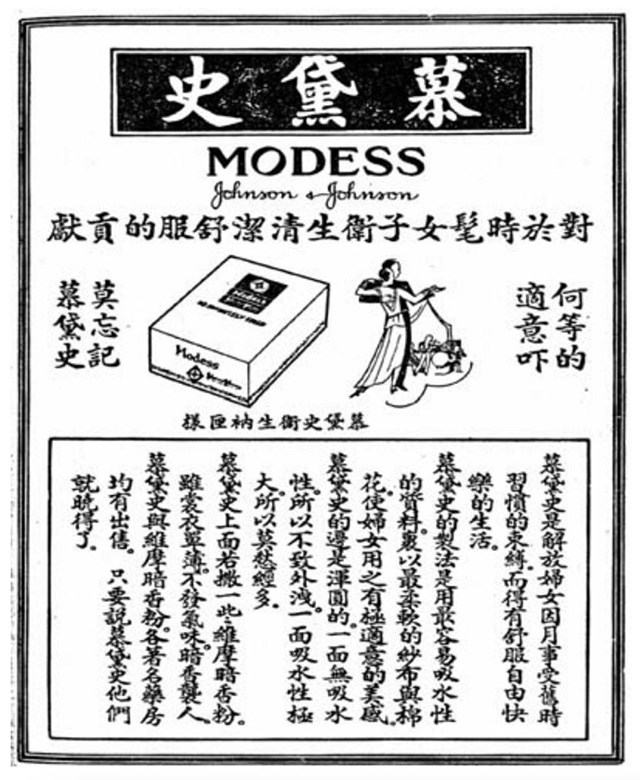

It was sooner than imagined that disposable menstrual pads entered the market of China in the Far East. By 1928, magazine advertisements of Kotex could be seen in popular Shanghai magazine Ladies’ Journal (婦女雜誌).[3] In later years, advertisements of other menstrual pad brands, including Modess by Johnsons & Johnsons and locally produced Comfort Sanitary Napkin & Belt (康福衛生棉衛生帶) could be found in the same magazine. But how was sales of these products? Expectedly, since it was mentioned earlier that menstrual cloth was mostly used among Chinese menstruators until the 1980s, sales of disposable menstrual products were probably disappointing. In her article on menstrual hygiene in contemporary China, Chou Chun Yen gave two speculative reasons: 1. It would have been too embarrassing for one to purchase menstrual pads in person; and 2. It was way too expensive.[4] In fact, the first issue was bothering menstruators across the Atlantic as well – sales of Kotex improved only after women could make a purchase by self-service: putting money in a payment box and taking their Kotex from the counter without having to speak to the shopkeeper.[5] It was likely that it was as difficult for Chinese menstruators across the ocean. But economic reasons might be an even larger factor. While menstrual pads were getting cheaper with the use of cellucotton locally, they were likely far from affordable in China as imported goods. The magazine ads also provide us a glimpse into the possible target customers of the pads: the fact that the ads were published in Ladies’ Journal, a magazine targeting upper-/middle-class Shanghainese women; that women portrayed in the ads were all modern-looking “fashionable” ladies (時髦女子) say a lot about who was targeted and was capable of using these newly imported 舶來品 goods.

Later, from the 1930s onwards, China entered a long period of war and political turmoil, and a switch to Communism. It was expected that cheaper ways to handle the menses, for example homemade menstrual cloth or paper made with straw pulp would have been much more popular than disposable pads. And we should remember that menstrual pads at that time was nothing like the ones we use today – they had no wings nor adhesive, so they would be more like a piece of cotton that is said to be designed to absorb menses, and needs to be attached to one’s panty or sanitary belt with strings or pins. Self-adhesive menstrual pads only appeared in the 1970s.

A Modern Dream, a Modern Way

The introduction of menstrual pads to China does not only reveal the life of the Shanghainese upper and middle class in the most prosperous city in China of the time. It manifests a paradigm shift of the Chinese scientific and medical arenas in their views of women’s biology, female hygiene and menstrual health, and their relationships with national survival as well as the individual menstrual experience.

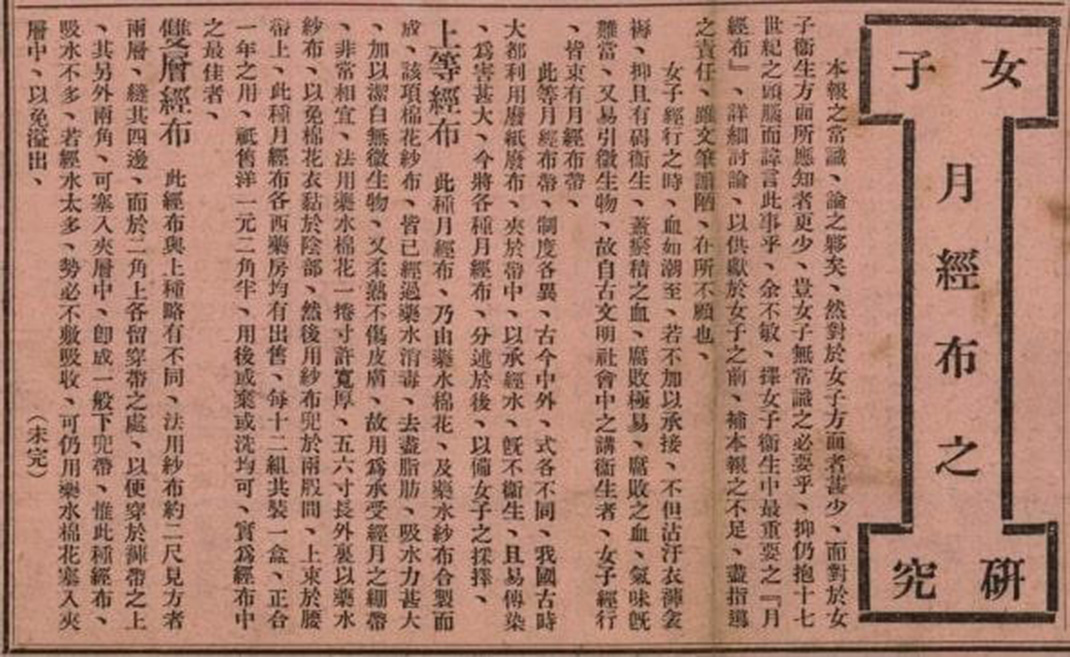

What came prior to the emergence of new “female hygiene” products was the flood of new, “scientific” notions of menstrual management and women’s health. The Republican period saw an unprecedented rise of public discourse in magazines about what menstruation is and how to manage it because of multiple reasons. The rise of modern publishing houses and women’s magazines in the country, the popularisation of Western medicine ideologies and the returning of overseas returnees who had received natural medicine education (in Japan, for example) all contributed to such an opening up of discussion of menstruation beyond medical books and involving the general public. The larger socio-political backdrop which involves an eager desire to strengthen the country amidst political turmoil and the start of a new regime, however, is not to be ignored. The late-Qing period had seen China being a weak Sick Man of Asia invaded by Western Powers, and Chinese intellectuals worried about their nation’s future and influenced by Western ideas of “survival of the fittest” and eugenics started to emphasise and promote the importance of strong female bodies for the continuity of the nation. As menstrual health is closely linked to fertility, it came to be a rising topic of interest among intellectuals, medical professionals (both Western and Chinese medicine), and the general public who had the privilege to buy and read women’s magazines. Although the discourse of menstruation has switched from explicitly political to more subtle, individual hygiene-oriented since the 1920s,[6] the line of thought pertained and the need of making women’s bodies healthier for producing better offspring was continuously emphasised.

Change Still Awaits

90 years later, today, menstruation in China is no longer just an issue of hygiene and fertility. Unlike the 1920s, Western biological medicinal ideas are well-learned in China today, and disposable pads are no longer ultra expensive and uncommon. But the question here is, does it mean that Chinese menstruators get as many good quality menstrual pads as they need? Unfortunately, the answer seems to be no.

In August 2020, a post on Weibo sparked heated debate on the price and quality of disposable pads in China. The original post by Weibo user Shangwang hairen 上網害人 showcases screenshots of a product page on Taobao and a thread of discussion in the product review section. The post is captioned “about menstrual pads, I only found out by accident that there are packageless menstrual pads for sale”, and the product featured in the screenshot is a bag of 100 menstrual pads put in a transparent zipper bag sold at 21.99RMB. What stirred public opinion was the second screenshot showing customer reviews, where a person has warned others of the potential risk of using such a product: “I suggest getting pads that are branded, how can you get anything this cheap for your private parts?”, only to have received replies like “life is tough” and “I have difficulties”.

This Weibo post has attracted thousands of other Weibo users to respond, some of them questioned the necessity of saving on menstrual pads as it costs “just the price of a bubble tea or a movie ticket”; some of them expressed empathy; some of them commented that it had never come to them that access to menstrual products is an issue: “I used to tease myself about not having money to get menstrual pads when I was a fresh graduate, now I know it is reality for some people”. Seems that the issue of period poverty is under the veil, but certainly is facing perhaps millions of menstrutors in China, where 600 million people earn only around 1000RMB per month and where menstrual products are taxed 13% (same as other consumer goods). The problem is likely accelerated by the COVID pandemic which has worsened the global economy. In Japan, media reports on the worsening situation of period poverty have caught attention last year, one year into the pandemic.[7] It is reported that Japanese students who rely on part-time income for a living have experienced a serious pay cut, to the extent that they must sacrifice expenses on menstrual products to buy food and to merely survive. In response to this, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare conducted an online survey on period poverty in the country this February. Results show that 8% of respondents have had difficulty accessing menstrual products because of financial reasons after COVID, and that they would change menstrual pads less frequently than suggested or use toilet paper as a substitute.[8] We can safely assume that in China, the situation would be even worse, and some struggling menstruators would resort to using extremely cheap menstrual pads without proper packaging sold online.

Habituating Payment

As mentioned above, until the 1970s, menstruators in China had been using homemade menstrual cloth or sanitary belts because of a lack of resources during the period of political turbulence. It was only in the 1980s after the Reform and Opening Up policy was launched that menstrual pads could finally be imported again after more than 50 years. In the 1980s, rising entrepreneurs in China also saw the huge opportunity and started their own menstrual pad production lines. One of the biggest and the first menstrual pad manufacturers in the mainland is Hengan Group established in 1985. Within years, disposable pads with self-adhesive that are more convenient than sanitary belts and a bunch of tissue paper; and more affordable than before have swamped the market. However, does it truly provide more convenience and make the lives of people who menstruate easier? Or does it narrow their options and make them think that disposable pads are the only and the best option, even if they cannot afford them? When more and more countries in the world are abolishing period tax or even providing menstrual products for free, and when the pandemic is still hitting hard in China (remember the “bleed a river of blood” incident at the beginning of this piece?), this is a pressing issue for the authorities to deal with.

Footnotes

- Donna Haraway, Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of women (New York, NY: Routledge, 1991).

- Harry Finley, “The first Kotex sanitary napkin ad campaign, 1921, and almost-the first Kotex ad (prototype, about 1920),” The Museum of Menstruation and Women’s Health, accessed April 20, 2022, http://www.mum.org/urkotex.htm.

- Lin Shing-ting, “‘Scientific’ Menstruation: The Popularisation and Commodification of Female Hygiene in Republican China, 1910s-1930s.” Gender & History 25, no. 2 (2013): 294-316.

- Chou Chun Yen 周春燕, “Zouchu jinji – jindai Zhongguo nvxing de jingqi weisheng (1895-1949)”走出禁忌——近代中國女性的經期衛生(1895-1949)[Getting rid of taboo – menstrual hygiene of women in Contemporary China (1895-1949)], The Journal of History, NCCU 國立政治大學歷史學報 28 (2007): 231-286.

- Harry Finley, “Inside MUM!” The Museum of Menstruation and Women’s Health, accessed April 20, 2022, http://www.mum.org/CuradsKotexads.htm.

- Lin, “‘Scientific’ Menstruation” 296.

- Huang Hsuan Shuo 黃宣碩, “Yiqing xia Riben ye mianlin ‘yuejing pinqiong’, wu fen zhi yi nianqingren juede fudan weisheng yongpin feiyong hen xinku,” 疫情下日本也面臨「月經貧窮」,五分之一年輕人覺得負擔衛生用品費用很辛苦 [“Period poverty” hits Japan also during the pandemic, 1/5 of teenagers find it hard to pay for menstrual products], The New Lens, March 19, 2021, https://www.thenewslens.com/article/148467.

- “Riben chao yi cheng nianqing nvxing ceng zaoyu ‘yuejing pinqiong’”日本超1成年輕女性曾遭遇「月經貧困」[Over 10% of young women in Japan have experienced period poverty], Nikkei 日經中文網, March 24, 2022, https://zh.cn.nikkei.com/politicsaeconomy/politicsasociety/48045-2022-03-24-1143-43.html.