Masks: UK. Breathe In, Breathe Out

Written by Francesca Bray

Published on 05/05/2020

It is too much to expect that under our British Bulldog leader Boris Johnson the United Kingdom would submit to learning anything from nations in East Asia. But as proud Brits Johnson and his ministers are equally averse to doing anything the same way as our erstwhile European partners. So here in the UK our leaders insist that face-masks are not just for sissies, they are positively dangerous.

Public wearing of face-masks in times of contagion – whether it’s the flu season or Covid-19 – is not an ingrained habit in Europe as it has become in most of East Asia. But that is changing fast. Face-masks proved their utility as part of an effective strategy to keep Covid-19 transmission down first in Slovakia and the Czech Republic, then in Austria. Now, as they feel their way into the lifting of lockdown, the governments of Italy, Spain and France are providing free face-masks for anybody using public transport and urging their use in shops and in the workplace. But in the UK a good month into lockdown, the government was still arguing that wearing face-masks risked increasing infection rates by encouraging the public to ignore physical distancing and neglect hand-washing, while the government agency Public Health England argued that wearing a mask could spread the virus and increase contagion because it makes people touch their faces more often.

Cynically, we could argue that one reason why our UK government and public health authorities so stridently proclaimed face-masks for the general public a safety risk is because for long enough they were unobtainable. No point telling people to do the impossible: that doesn’t raise approval ratings in a crisis one little bit.

For weeks you couldn’t buy masks in any chemist’s in Edinburgh, big or small – even the staff didn’t have them until a month or six weeks into the crisis – and even Amazon was unable to supply them. My own came by overseas mail, courtesy of friends in Hong Kong and China, and I shared them with a neighbour who is a hospital doctor until at last her workplace obtained a supply.

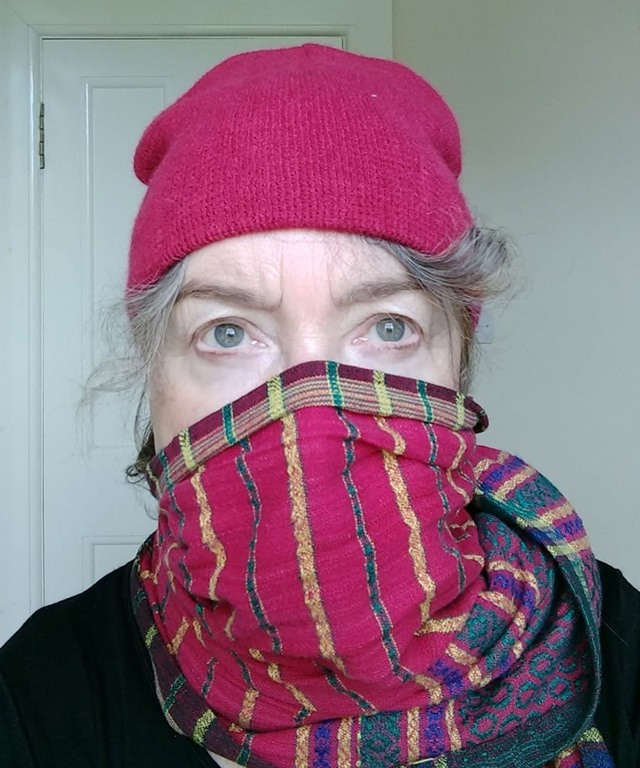

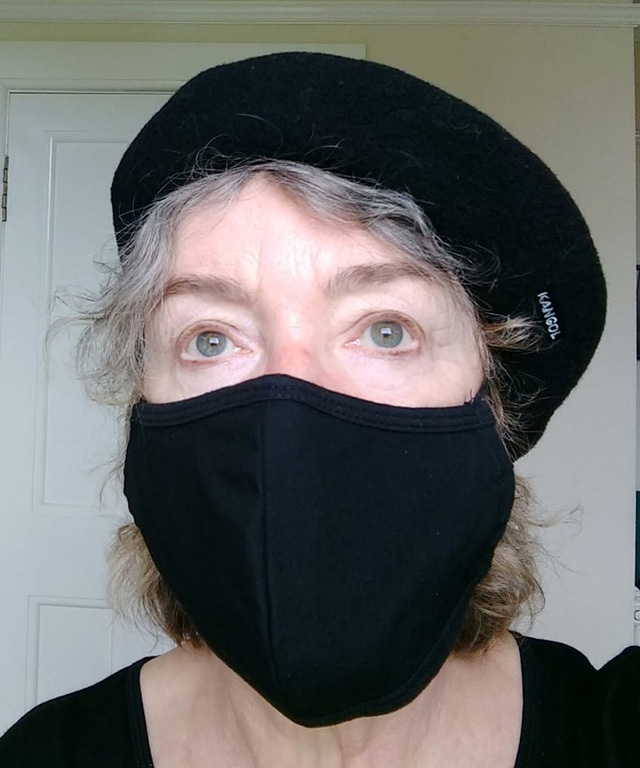

Nevertheless, despite the steady stream of official pronouncements that masks do more harm than good, there has been a steady increase in the proportion of people in supermarkets or on the streets wearing some kind of face covering. At first when I went on my (strictly rationed) trips to the supermarket, the only people wearing masks had East Asian features. The last time I joined the queue, which snaked round the block because of the 2m distancing rule, almost everybody was wearing a face-covering of some sort: some people had scarves wound round their lower face, others wore light disposable masks, home-made cloth confections, or even heavy-duty PP3 masks.

As I’m in lockdown I have little opportunity to judge how typical our South Edinburgh shopping-mall community is. I do wonder if our embrace of face-mask culture has something to do with the proportion of East Asia-connected inhabitants in the local population. Edinburgh’s universities and schools are very popular with students from the PRC and elsewhere in East Asia, and the city has one of the oldest and largest British-Chinese communities. They have all been wearing masks from the start, regardless of curled lips and sideways glances on the buses. Has their example helped the community to assimilate a new normal? Who knows, but the Scottish government has now officially recommended wearing masks ‘in places where social distancing is difficult[1]. The Westminster government is still ‘considering the evidence’.

And yet, while it might seem that the Westminster government, here as elsewhere, is going it alone, in this case it has WHO backing. WHO still does not recommend wearing masks for healthy members of the public, arguing that there is little evidence for masks providing the wearer with serious protection from contagion. So why have governments in France and Spain changed their minds about the value of WHO recommendations? Two public health researchers writing in The Conversation on 5 May identified the contradictions in advice about masks as the tension between two basic public health principles: the principle of effectiveness says that unless a specific action is proven to work then it should not be advised; the precautionary principle says that ‘doing something might be better than doing nothing.[2] But I think the contradiction goes still deeper.

The anti-mask position is primarily based on calculations of how likely different types of mask are to stop the virus getting in, not how effective they are in blocking it from getting out. I find this a fascinating way to reason about epidemics: the assumption is that the primary way to control the disease’s spread is to protect healthy individuals from infection by providing them with impenetrable defences. Anything less efficacious is deemed useless, or worse still, counter-productive – and as the masks that are most effective at preventing inhalation of particles are expensive and in short supply, it is indeed rational to restrict their use to medical personnel and other front-line carers. Yet even WHO agrees that simple face-masks considerably reduce the risk of an infected person spraying the air around them with droplets carrying the virus. They also acknowledge that infected people are highly contagious for three or four days before they develop symptoms, and that many infected people are asymptomatic. So encouraging people without symptoms to wear face-masks seems a no-brainer when viewed from the goal of protecting the community, as opposed to protecting the individual. Prioritising breathing in or breathing out as the most effective point of intervention is, like any medical policy, a political choice.

Footnote