Shuanghuanglian Oral Liquid: TCM Pharmacotherapy in the Time of Coronavirus

Written by Xiaomeng Liu

Published on 15/03/2021

On the evening of January 31, 2020 — the seventh day of the lunar new year — news broke and spread rapidly on the Chinese social media platform WeChat regarding a certain shuanghuanlian koufuye (双黄连口服液, hereafter SHL oral liquid) showing efficacy in inhibiting the “novel coronavirus pneumonia” (xinguan feiyan 新冠肺炎), which had come out of Wuhan and was wreaking havoc. In a normal year, the seventh day of the lunar new year would be the day that people return back to work after the Spring Festival; instead, in 2020, most Chinese people were grounded at home awaiting further updates on the coronavirus (later labeled “COVID-19”), and the holiday had been effectively extended.

What the news was about was that preliminary lab research results released by the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica (SIMM) and Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) had shown that shuanghuanglian oral liquids, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) patented drug, demonstrated to be effective against the coronavirus. Upon seeing the news, Chinese people rushed to pharmacies for the drug or to online platforms to order it. Every pharmacy regardless of location ran out of inventory within mere hours.

The authorities immediately took notice of this panic purchase, and on the next day, the People’s Daily posted on Weibo (Chinese social media platform similar to Twitter) an advisory, urging ordinary citizens to refrain from using the SHL oral liquid without first consulting a TCM doctor. The post also cited the WHO’s earlier caution that up to that point there were “no effective drugs that [could] be used to prevent or cure COVID-19…” Other major media outlets also disseminated the general view of medical specialists: that what preliminary lab research they knew of or could find at that point regarding the SHL oral liquid could not be considered conclusive proof for its efficacy in clinical treatment.

The panic purchase thus subsided quickly, and SIMM and WIV further conceded to the public that they needed more clinical trials before they could confirm the drug’s efficacy. This however did not extinguish Chinese people’s enthusiasm to buy TCM drugs that were said to be effective for COVID-19. The next most-coveted star drug was the lianhua qingwen jiaonang (连花清瘟胶囊 (capsules), hereafter LH capsule(s)), whose clinical trial results Zhong Nanshan (钟南山) — a hailed national hero for leading the fights against SARS and COVID-19 — publicly discussed with European medical specialists during an online meeting. Also on the list of favorites for Chinese people both inside and outside mainland China was Banlangen (radix Isatidis) compound granules (fufang banlangen keli 复方板蓝根颗粒), a patented TCM drug that gained (super)stardom from the 2003 SARS outbreak.

Why are the Chinese people today so tantalized by the idea that herbal-based TCM drugs can be effective remedies for new, even acute diseases, despite a general lack of scientific studies or evidence to support such claims? Such cravings of the populace for effective TCM drugs as antidotes to epidemics traces back to before the COVID-19 epidemic. I still remember that, during the SARS outbreak in 2003, a certain herbal decoction sold in my hometown for several hundred RMB (which was fairly expensive) claimed to be an effective preventative for the virus. What is more interesting to observe from all this, is how public confidence in TCM remedies which developed over the last two decades, coupled with increased official endorsement from the state, has — as was evident during the COVID19 pandemic — elevated TCM to being perceived as a modern, legitimate system of medicine. This stands in stark contrast to past clichéd notions that TCM was a pseudo-medicine only (tepidly) effective against chronic conditions, and was an “option” that people should only resort to when they had run out of all biomedical alternatives.

Indeed, traditional Chinese medicine has had a long history of treating epidemics and contagious diseases dating back to at least the second century. In republican and contemporary China, TCM experts used to frequently consult historical medical schools of thought, such as cold damage disorder and warm disease, to make sense of modern contagious diseases.

Fast forward to times of the COVID-19 epidemic: the disease was preliminarily identified by a preeminent TCM expert as a hanshi yi (寒湿疫), an epidemic induced by cold, damp qi. Such prognosis drew on TCM theory that diseases are caused by seasonal pathological qi, and only by identifying the nature of the pathological qi can experts formulate effective remedies. However, first of all, this prognosis was not conclusive. Second, as TCM specialists continued to actively participate in treating COVID-19 patients, their diagnostic interpretations and therapeutic strategies also evolved constantly.

It is not the intention of this essay to reiterate such dichotomies as biomedicine versus alternative medicine, and traditional versus modern views. Nor is it helpful to question the rationality and efficacy of TCM treatment from the perspective of modern bioscience. Instead, the essay will briefly examine how TCM pharmacotherapy was implemented, developed, and valorized during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in China.

State-sanctioned TCM Formulae and Resulting Business Opportunity

On January 22, 2020, just one day before Wuhan went into lockdown, the National Health Commission (NHC) and the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (NATCM) co-issued the third trial edition of the Scheme for Diagnosis and Treatment of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (hereafter Scheme). Unlike the first two trial editions, this one added a substantial section on treating COVID-19 — TCM treatment.

Unlike previous identification of cold and dampness epidemics, the Scheme claimed that the characteristics of COVID-19’s pathogenesis was “damp, hot, toxic, and stagnant.” It listed four patterns identified from COVID-19 patients; under each pattern were four sub-sections: symptoms, treatment method, recommended formulae, and basic herbs in the formulae. All of the eleven recommended formulae were derived from either the works of the cold damage or warm disease tradition, the two main schools of thought in Chinese medical theory in dealing with epidemic diseases both of the past and the present. The sources of these formulae date back to as early as the second and as late as the 18th century. Nevertheless, even if the origin of a formula dates back for hundreds of years, it does not mean that it has remained unchanged over time. Some of them have undergone minor changes and entered into various medical and recipe books at different times under incongruent versions. Physicians and pharmacies in late imperial China also had individual adaptations of practice. It was not until the 1950s and 1960s that the China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine attempted to compile and standardize the use of TCM formulae in the country.[1]

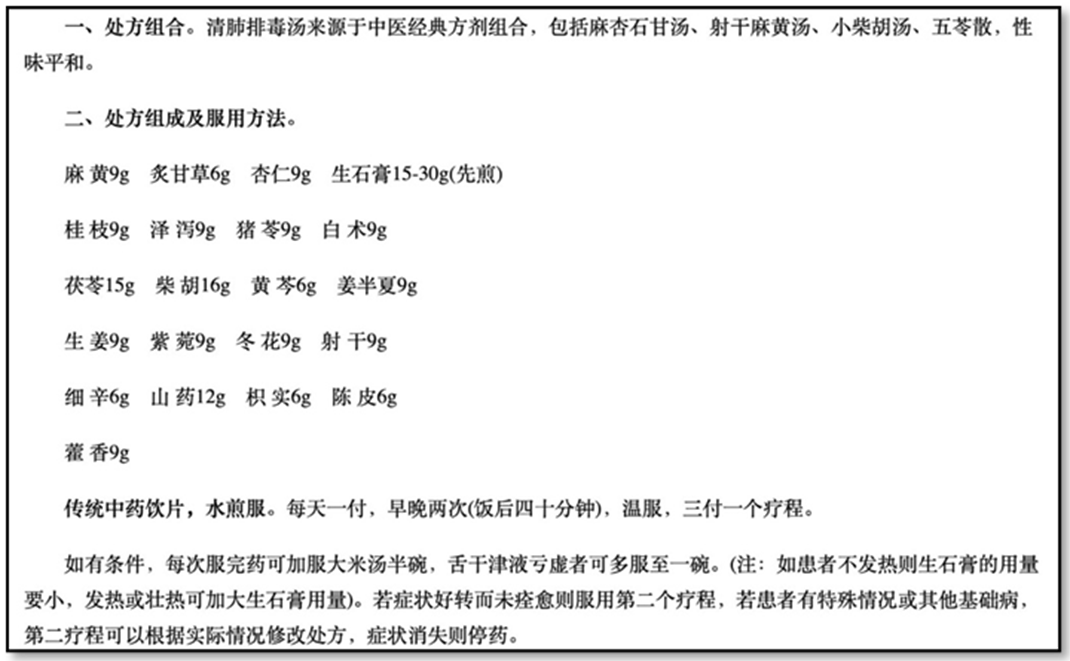

In contemporary practice, classical, established formulae are conventionally used by TCM doctors as bases for their prescriptions, in other words they are subject to adjustments and adaptations according to the specific conditions of each patient. On February 6, 2020, the NHC and NATCM recommended a formula called qingfei paidu tang (清肺排毒汤, “decoction for clearing lung-heat and detoxification”), a new formula that combined five established formulae from classical medical works. This formula was also added to the sixth edition of the Scheme (released February 18, 2020) as the first recommended formula that could be used to treat COVID-19 patients exhibiting different patterns and conditions.

Between January 16 and February 18, the NHC and NTCM released six editions of the Scheme. Afterwards, updates of the Scheme slowed. The seventh and eighth editions were respectively released on March 4 and August 18, 2020. From the fourth edition onward, the Scheme would continue to specify the cause of COVID-19 as an epidemic qi, but would no longer define the nature of that qi. It also differentiated patterns according to the process of disease development. From the sixth trial edition, the Scheme switched to categorizing different patterns according to patients’ conditions — mild, common, severe, or critical. In line with these diagnostic changes, the recommended formulae for each pattern also changed from established ones to customized prescriptions. The names and amounts of every ingredient, the method to prepare the decoction, and intake directions were outlined.

How the diagnoses and formulae changed over the course of the eight editions of the Scheme sheds light on how TCM specialists adjusted their strategies toward treating and preventing COVID-19 early on. Another noteworthy introduction to the fourth and subsequent editions was the “Period of Medical Observation” subsection before “Clinical Treatment” in the TCM section. The drugs mentioned there were not TCM formulae but patented drugs in the form of capsules and granules. LH capsules were an example.

The formulae and patented drugs listed in the Scheme were meant to be used in clinical treatment under the guidance of specialists, as opposed to being self-administered as preventives by ordinary people. The NHC and NTCM never intended to publicly disseminate them in the first place. However, in the first two months of the COIVD-19 outbreak in China, local governments and hospitals in, for example, Guangdong and Zhejiang provinces disclosed preventive formulae to the public, and local TCM pharmacies and herbal dealers were keen to identify the public’s craving for effective TCM-based COVID-19 remedies as a business opportunity. They packaged herbs and bottled herbal decoctions that were produced based on different recommended formulae, including those obtained from the Scheme, and sold them through social media and online shopping platforms.

There is a downside to these preventive herbal formulae — they are not convenient for mass production or dissemination. In fact, the best-selling TCM drugs during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak were neither herbal packages nor decoctions, but were patented drugs that had already been on the market for several decades. On the other hand, none of the three star TCM patented drugs mentioned above were based on old, existing formulae. Instead, they were developed and popularized after the 1980s.

Origin and Rise of a Recent Star Patented Drug

Here, SHL oral liquids are used as an example to illustrate the process of deriving and developing successful TCM pharmaceutical products out of folk recipes. SHL oral liquids are an over-the-counter (OTC) drug and can be prescribed by a TCM doctor to treat a common cold or flu whose symptoms suggest that it is caused by wind-heat (in contrast to wind-cold). The reality, however, is that the Chinese people seldom see a doctor for a common cold; they would simply self-diagnose any symptoms of fever, sore throat, and coughing as “having excess heat in the body” and obtain the medicine directly from a pharmacy.

SHL oral liquids are a patented drug, and as evident from the name “SHL,” it consists of three main herbal ingredients: shuang, which stands for shuanghua (双花) or jinyin hua (金银花), otherwise known as honeysuckle (including several species of the genus lonicera); huang, which refers to huangqin (黄芩), a.k.a. Chinese skullcap (Scutellaria baicalensis); and lian, which is short for lianqiao (连翘), and is commonly called golden bell (Forsythia suspensa). According to TCM theory, the particular formula can expel pathological wind, relieve exterior symptoms, cleanse one of excess heat, and detoxify.

A formula that comprises only three common herbs is simpler than usual. TCM formulae commonly contain four categories of ingredients: the monarch (jun 君), the most effective part of the treatment against the primary symptoms; the minister (chen 臣), who is an aide to the monarch; assistants (zuo 佐), who are supposed to reinforce the power of the monarch and the minister; and guides (shi 使), which are substances that facilitate and usher the “actuators” to the right places in the body. The SHL oral liquid’s formula does not follow this principle at all, and this fact indicates that SHL oral liquids were not developed by elite doctors, but were most likely the result of folk healing practices. The banlangen compound granule is even simpler in this sense, containing merely two ingredients, banlangen and daqingye, which are the roots and leaves of isatis tinctoria, a common herb that is also used as a blue dye.

Such herbs are native to and commonly found in different parts of China. They are widely used in folk healing practices as anti-inflammatory and febrifugal elixirs by the populace. During the Sino-Japanese War of the 1940s, the army led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had a shortage of medicines especially antibiotics. In a quest for substitutes, the medical bureau of the CCP attempted to develop anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and febrifugal drugs from common herbs.

The first successful product was an injection made from a herb common in northern China called caihu (柴胡, bupleurum chinense). This success inspired several other herb-based injections in the following years, including a banlangen injection. In the early years of the People’s Republic, herb-based injections were also considered the new direction towards which TCM should be modernized. Injections made from SHL began to be in use in 1973.[2]

In the 1970s and early 1980s, SHL shots were mostly produced by several pharmaceutical plants in Harbin, the capital of Heilongjiang Province. In 1988, the Harbin Second Pharmaceutical Plant started a new project to improve the manufacturing process and quality of these SHL injections. In collaboration with the Heilongjiang College of TCM, the plant developed a new method to change the traditional liquid injection into a powdered injection. This was the first such TCM-based powdered injection, and it was soon put into mass production and clinical use. In total, 629,700 doses were sold within the first year of its formal release.[3]

However, the SHL injection had its obstacles toward becoming an ultra-successful product: the injection requires assistance from a medical professional. Thus, its use is confined to hospitals and clinics. A few years later, the Harbin Third Pharmaceutical Plant released their own version of SHL product, an OTC oral liquid that was easy to ingest by consumers on their own. Of all branches of the Harbin Pharmaceutical Group Holding Company, the Third Plant became most successful and famous in the 1990s and 2000s. Advertisements of their products were regularly seen on TV, and both their OTC drugs and food supplements became very well-known among Chinese families.[4]

The banning of phenylpropanolamine (PPA) as a common cold medicine in 2000 provided an excellent opportunity for SHL oral liquid to take the lion’s share of the medical market. Based on research findings from a group of Yale medical researchers, the USFDA issued a public health advisory in 2000 against the use of PPA, as it would increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. The Chinese government also responded quickly within the same year to suspend the sale of any medications containing PPA. This imposed an unprecedented crisis on SK&F, a pharmaceutical company in China co-founded by global pharmaceutical giant GSK and two local companies in Tianjin. Their top product, Contac (ch. kangtaike 康泰克), one of the most popular OTC drugs for the common cold in China, had to be taken off shelves in pharmacies. The Harbin Third Pharmaceutical Plant seize the opportunity to launch a big promotional campaign for their SHL oral liquid. At that time, 13 pharmaceutical plants in China had approval to manufacture that product, but the Harbin Third Pharmaceutical Plant was the leader in sales, owing to this successful marketing strategy.

Bridging Ancient Wisdom with Bio-science

In a world where public health systems are dominated by modern biomedicine, the efficacy of using TCM-based drugs to treat and prevent COVID-19 can only be “validated” through state recommendations, public recognition, and commercial success, but has no definite proof. Even though many TCM specialists in China resisted the idea of using biomedical theory and technology to explain and valorize the efficacy of TCM drugs, it is still unrealistic to cite only TCM theory to convince state officials and biomedical specialists to use them in any public health crisis. In fact, bio-scientific research will prove indispensable especially when the Chinese central government wanted to introduce the patented TCM drug for COVID-19 to other parts of the world.

The successful discovery of artemisinin may offer an excellent model for the bioprospecting of Chinese herbs, as the course this discovery represents the preferred way of translating ancient wisdom into bio-scientific facts, which is to isolate chemical compounds that are effective in treating certain ailments. Before the case of artemisinin, many TCM specialists and biomedical scientists had already followed this direction but had achieved very limited success. To be sure, singling out active components in Chinese herbs is very difficult and problematic, not the least because, as many specialists nowadays agree, the majority of Chinese herbs have multiple active components, and it becomes tremendously complicated to isolate and determine how each reacts and interacts with other substances inside the human body. In fact, even though the Chinese Pharmacopeia lists one to several key chemical compounds in each of the herbs in its compilation, we are still a long way from confirming that all of them are actual active components that treat diseases.

In the face of such difficulties, some pharmaceutical companies in China attempt to confirm the efficacy of their TCM products using another path — through clinical trial. In contemporary pharmaceutical development, clinical trial is a standard way to test the efficacy and safety of pharmaceuticals before they are formally released into the market. A standard clinical trial consists of five phases: the initial Phase 0 and the last, post-marketing Phase IV are optional. All pharmaceutical companies otherwise need to conduct the core three phases of the clinical trial on their products before they will obtain approval from the FDA. Using clinical trial on TCM drugs can bridge ancient wisdom with modern bio-science: though the active components in a herb-based pharmaceutical may not be fully ascertained, the overall efficacy can nonetheless be proved by rigorous, stringent clinical trials.

One TCM product did try to get approval from the USFDA — Danshen Dripping Pills, a patented flagship product of the Tasly Pharmaceutical Company in Tianjin used for treating unstable angina pectoris and coronary heart disease. Tasly rebranded the drug as Dantonic and filed an application to the FDA in 1997 for approval. In 2016, after 21 years, Phase III of its clinical trial was finally completed. However, although Tasly claimed that the clinical trial was a success, it actually failed to obtain approval from the FDA. The data from the clinical trial could not confirm the drug’s efficacy.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 epidemic, Chinese scientists and TCM specialists have started to select potential TCM formulae and patented drugs to conducted lab tests and clinical trials on. SIMM and WIV were the first to release to the public their preliminary results on SHL oral liquids. However, unexpected public reactions forced them to clarify that their results had demonstrated the drug’s effectiveness in inhibiting the replication of the COVID-19 virus during in vitro tests only. They were still a long way from putting their research to clinical trials.

On May 16, 2020, a Chinese team led by Zhong Nanshan, Zhang Boli, and Li Lanjuan, three top scientists in the fight against COVID-19, published an article in Phytomedicine to present their clinical trial result on the efficacy and safety of LH capsules in treating COVID-19 patients. The result showed that the treatment group who took LH capsules with other antiviral medication had a significantly shorter period of recovery than the control group, who used only standard antiviral medications.[5] Before the clinical trial, another group of Chinese scientists had demonstrated the LH capsules’ efficacy against the novel coronavirus in in vitro tests.[6] The successful result was touted on Chinese media as significant proof of the drug’s efficacy against COVID-19. It also made LH capsules a hot selling product in pharmacies.

LH capsules are produced by the Shijiazhuang Yiling Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. It is said that the formula was concocted by Wu Yiling, a renowned TCM specialist and founder of the company, during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Two years later, LH capsules were approved by the Chinese FDA and were sold as medication for common cold and flu. It further went from being a prescription drug to an OTC drug in 2007. After successfully using LH capsules to treat COVID-19, China also tried to promote the product to other parts of the world.

However, the design of the clinical trial was obviously flawed: particularly, it was not a double-blind trial, and there was no placebo control group. The article explains that the rapid outbreak of COVID-19 made double-blind and placebo-controlled trials unrealistic and unethical. As such, a more comprehensive study was still needed to further explore the effects of LH capsules. These cases demonstrated the difficulty to translate the efficacy of TCM drugs into a fact of bio-science. Some may even claim that such translation is not possible at all. Nonetheless, TCM specialists and Chinese scientists today, like their predecessors in republican China, keep an open mind and adopt a flexible strategy to integrate TCM with biomedicine. TCM specialists in China today frequently speak of TCM as ancient wisdom embodying thousands of years of experience from their ancestors. Even though they cannot explain the efficacy of many substances in biomedical terms, the accumulated experience can at least validate TCM’s therapeutic value. They often resort to using a simple but potentially powerful claim: “TCM works in practice.” Surely, to medical professionals, this empirical attitude toward TCM is not good enough for demonstrating its legitimacy let alone superiority. Nor is it not good enough for a state to promote it to the rest of the world. In any event, the endeavor to find commensurability between TCM and biomedicine is still going strong; the COVID-19 outbreak has only made this endeavor ever more compelling.

Footnotes

- The efforts resulted in an edited volume recording more than 2,000 formulae that were collected from pharmacies from 25 cities in different parts of China. Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine eds., Quanguo zhongyao chengyao chufang ji 全国中药成药处方集 [A national formulary of TCM patent drugs in China] (Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House, 1962). The China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine changed its name to the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences in 2005, on its 50th anniversary.

- Zhang Boli 张伯礼 and Chen Chuanhong 陈传宏 (eds.), Zhongyao xiandaihua ershinian: 1996–2015 中药现代化二十年:1996–2015 [Modernization of traditional Chinese drugs: a twenty-year review, 1996–2015] (Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 2016), 278–279.

- Yue Yuquan 岳玉泉 et al., Haerbin shizhi 哈尔滨市志 [Gazetteer of Harbin] volume on the textile industry and medicine (Harbin: Heilongjiang People’s Press, 1996), 342.

- Cao Gang 曹刚 et al., Guoneiwai shichang yingxiao anli ji 国内外市场营销案例集 [A collection of domestic and foreign cases on marketing] (Wuhan: Wuhan University Press, 2002), 165–167.

- Hu, Ke et al., “Efficacy and safety of Lianhuaqingwen capsules, a repurposed Chinese herb, in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trial,” Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 153242. 16 May, 2020, doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153242.

- Runfeng, Li et al., “Lianhuaqingwen exerts anti-viral and anti-inflammatory activity against novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2),” Pharmacological research vol. 156 (2020): 104761. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104761.