Covid Testing and Mask Wearing: Rebuilding Everyday Life — China’s Routinized Epidemic Prevention and Control

Everyday life in China’s post-epidemic era is restructured through routinized epidemic control.

Written by Chaoxiong Zhang

Published on 18/05/2021

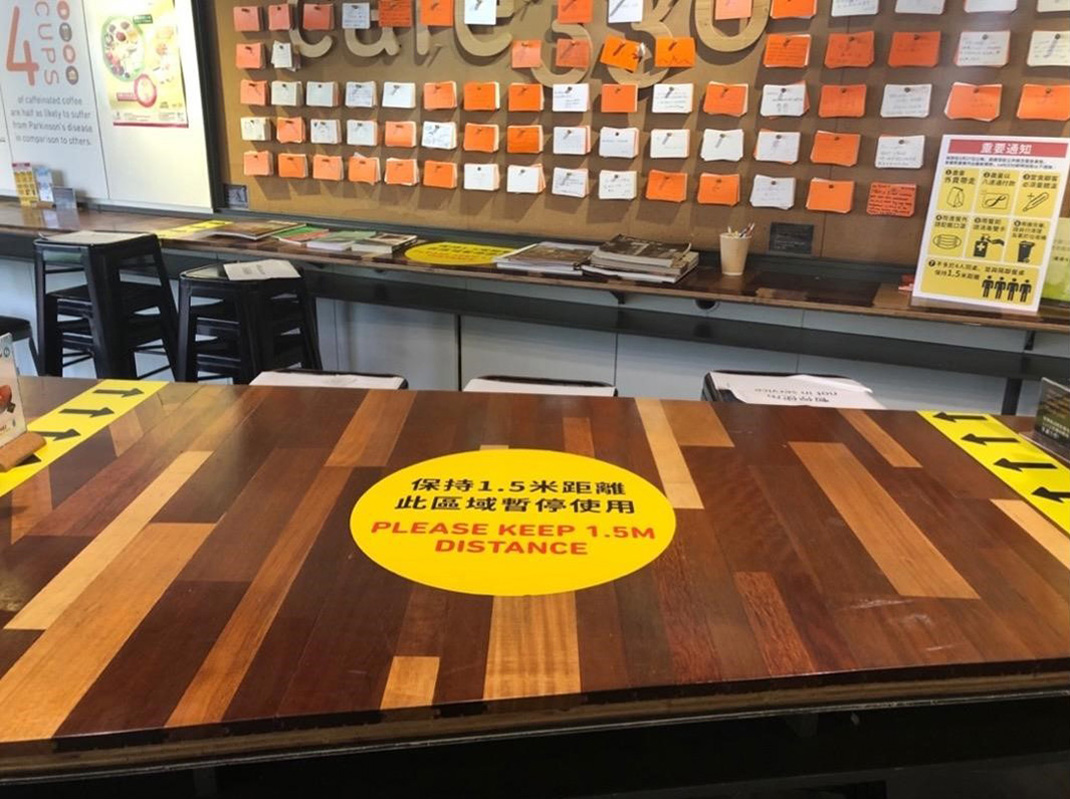

Despite the resurgence of COVID-19, people’s daily routines in China appear to be gradually returning to normal. However, many norms have already been broken, and the old “normal” may never return. Our minds have built invisible rulers that measure the size of the virus and the distance that droplets can reach; we have installed internal timers that count down the virus’s life span and incubation period; we have adjusted our impressions of public spaces and our positive attitudes towards social gatherings. Throughout the epidemic, perceptions of space and time have changed; we can no longer take our former routines for granted.

With the current pandemic, sporadic locally transmitted cases, and the mutating coronavirus, we are forced to live with the virus, and the uncertainty it brings. On May 7, 2020, the Chinese State Council Cooperation Mechanism on Joint Prevention and Control of COVID-19 (國務院聯防聯控機制) issued the Guiding Opinions on Routinizing COVID-19 Prevention and Control Work (關於做好新冠肺炎疫情常態化防控工作的指導意見).[1] How has the new normal been constructed during the routinized prevention? How have everyday lives been organized and navigated in the new normal of time and space? What technologies and strategies have been adopted to cope with these challenges and enable a return to our daily routines?

Wuhan Citywide COVID-19 Testing: The “Return” to Society

In early May 2020, one month after the end of the Wuhan lockdown, a small community outbreak broke out in Wuhan’s Dongxihu District. On May 12, 2020, the Wuhan government released the “Emergent Notice on City-wide New Coronavirus Nucleic Acid Test Screening” (關於開展全市新冠病毒核酸篩查的緊急通知). In response to this notice, a “ten-day battle” to test everyone for COVID-19 was set in motion. As of June 1, Wuhan has tested almost 10 million residents, and has reported a total of 300 asymptomatic cases. Although many residents have supported the screening, some have been concerned about the effectiveness of such a costly project. Many have also expressed their fear of being exposed to the virus through contact during testing. One of the primary concerns is nucleic acid test’s diagnostic accuracy. Although nucleic acid test is the “gold standard” for COVID-19 diagnosis, many people have had terrifying memories of false-negative results that were prevalent in the early stages of the outbreak. Thus, they have questioned whether the citywide test can screen out asymptomatic carriers, especially under such a short time frame. Others have questioned that even if the test can identify asymptomatic carriers, to what extent can it prevent another epidemic. In other words, is it necessary to conduct such a large-scale screening?

Several public health experts have also questioned the “scientificity” of the battle, and suggested that the Wuhan government should make the decision based on more scientific methods such as statistical sampling.[2] However, as Zhang Wenhong, head of Shanghai’s COVID-19 clinical expert team has suggested, citywide testing is not only to fulfill a medical need but also for social demands.[3] The city of Wuhan and its residents have suffered from fear, anxiety, anger, hopelessness, grief, and isolation. Although the slogan “Go Wuhan!” is ubiquitous and Wuhan’s residents have been praised for their sacrifices, they have still suffered stigmatization from being associated with the novel coronavirus and its related risks. Indeed, due to the existence of asymptomatic cases, everybody is a potential carrier. The end of the lockdown on April 8, 2020 has not stopped the social exclusion, discrimination, fear, or anxiety—there are still many barriers to Wuhan residents’ resuming their daily routines. A mutually recognized social end to the epidemic, and a mutually recognized social restart are needed for the return and rebuilding of everyday lives.

The citywide testing helped to address individual psychological demands for confidence and trust. After receiving their testing results, many Wuhan residents would share them on their WeChat Moments or neighborhood or work WeChat groups. Many people considered taking the test to be a responsibility for the safety of both themselves and their peers. The test results have functioned as a health code to show that it is safe for them to socialize and to return to their regular community lives. Thus, sharing the results has also become a “ritual” that signifies an end of the chaotic past and a refreshing new start. The new start is also crucial for Wuhan as a whole. Citywide testing in Wuhan has reassured residents, and those in other areas, that the city is safe and that there is no reason for social fear or prejudice. As Wuhan Deputy Mayor Hu Yabo said, “The screening has reassured people all over the country (that Wuhan is safe). The cost is well worth it…the success of this screening has displayed once again the heroism of the city and its residents.”[4] After the screening, this hero city is ready to return and move on.

By providing free tests for all, the city-wide screening also contributes to a mutually recognized social end to the epidemic by displaying that the government has followed the governing philosophy of “people first”, and has taken responsibility and care for its people. At the same time, the government has also sent a message to the international community that China has exerted unremitting effort and has made enormous achievements in conquering the outbreak. As China’s leading epidemiologist Li Lanjuan has said, “Wuhan’s nucleic acid test has covered almost the entire city, (which has been) a huge and rare (success), even on the global scale. The result of the citywide testing will play an important role in guiding epidemic prevention and control, in both China and across the globe.”[5]

The medical, psychological, and political effects of the test have legitimized a mutually recognized social end to the epidemic. In turn, this has facilitated calls to restart the economy. As the epidemic has eased, economic recovery has become the priority. Many have agreed that the battle against the epidemic cannot be considered a complete success until the economy has resumed. Although there are many concerns about the effectiveness of the citywide COVID-19 testing, the test has provided a scientific basis for legitimizing routinized epidemic prevention and economic recovery-related policies.

Returns to normalcy and society are difficult for individuals, the city, and the country as a whole. Wuhan’s “ten-day battle” is not merely a fight to screen out potential virus carriers or an epidemiological investigation. The mass COVID-19 testing has also been an attempt to fulfil the social, psychological, political, and economic demands of returning to normalcy, returning to productive lives, and rebuilding daily routines.

Wearing (or Not) Masks: The Sustaining of Normalcy

The citywide COVID-19 testing has revealed the power of transition in facilitating return to ordinary routines. Another “everyday technology”, masks, has played an important role in living with the virus and allowing daily routines to persist. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, debates over masks were absent from the discourse of daily routines. Wearing a mask might indicate that an individual was sick, but sickness like cold or flu was an established component of our daily lives. Also, in many locales, mask-wearing had already become ordinary after various public health crises. For example, in Northern China, such as in Beijing, toxic smog, has led to people stocking masks in their homes.

However, due to the infectious nature of the COVID-19 outbreak, wearing masks is no longer an individual health concern. In some places, people wearing masks are viewed as a threat and a source of infection. In others, such as China and many other Asian countries, wearing masks has already become normative. Not wearing masks has been viewed as irresponsible behavior, and has even been subjected to moral censure.

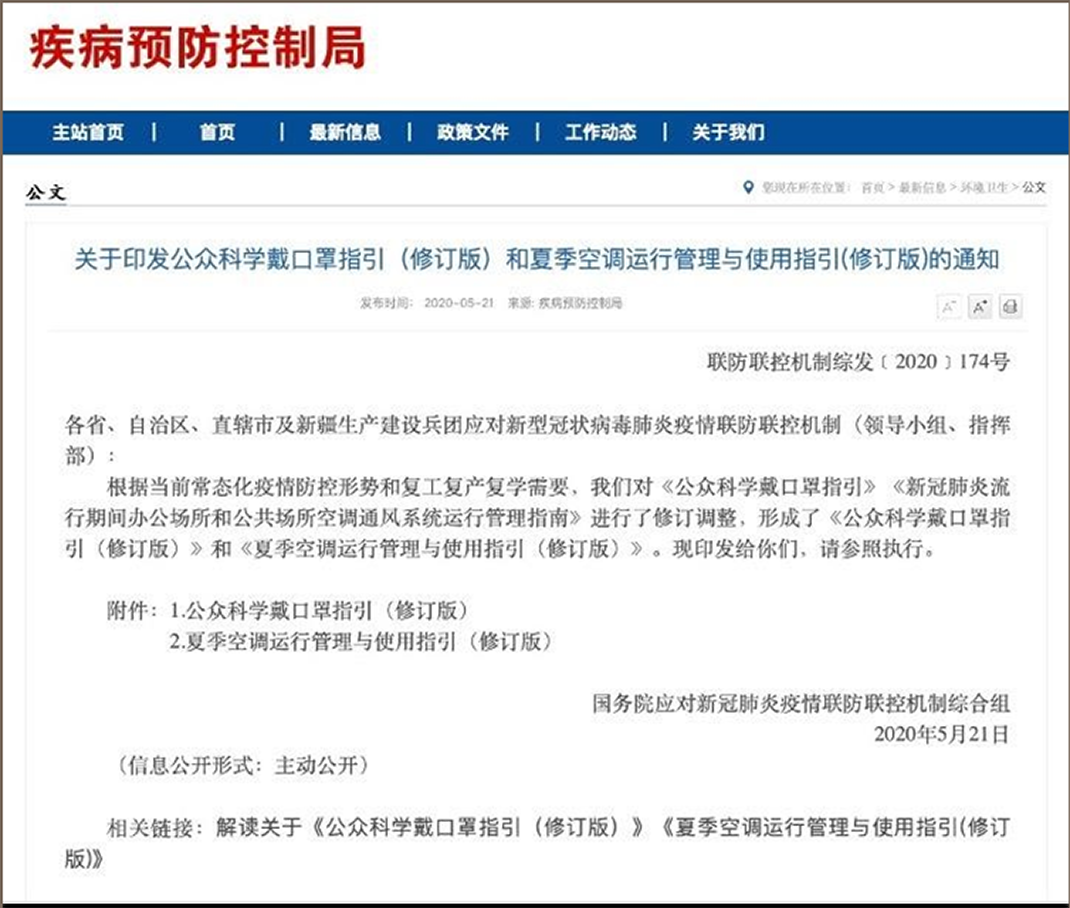

With the abatement of the epidemic and the coming of hot weather, many people think it is already time to remove masks and return to “normal”. Yet as mask-wearing has already become a social and moral norm, removing them is no longer an individual decision. People need to wait for a morally and socially recognized time, which is often endorsed by experts’ suggestions or official announcements. For example, the State Council Cooperation Mechanism on Joint Prevention and Control of COVID-19 issued an updated version of “Scientific Guidance on Wearing Masks” (關於印發公眾科學戴口罩指引修訂版) on May 26, 2020. The instruction states which populations need to wear masks, and under what circumstances.

Many matters are taken for granted in our everyday lives. However, the COVID-19 outbreak has changed much of what we perceived as normal. We have developed new norms and techniques which have enabled us to cope with the public health crisis, and continue with our daily routines to stay healthy and safe. These technologies have enabled the resumption of our daily routines. However, these coping technologies have been routinized, and now define the new “normal”. Indeed, the routinization of one domain of everyday life can affect other domains by obscuring the boundaries between public and private, public health and public security, governance and surveillance. Debates over these issues challenge the rebuilding of everyday life, and perceptions of the social end of the epidemic in the post-epidemic world.

Footnotes

- Chinese State Council Cooperation Mechanism on Joint Prevention and Control of COVID-19 國務院聯防聯控機制, “Guanyu zuo hao xinguan feiyan yiqing changtaihua fangkong gongzuo de zhidao yijian” 關於做好新冠肺炎疫情常態化防控工作的指導意見 [Guiding Opinions on Routinizing COVID-19 Prevention and Control Work], May 8, 2020, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/202005/08/content_5509896.htm.

- Tang Peilan 湯佩蘭, “Wuhan quanmin hesuan jiance, ranhou ne? Xiayibu shi shenme?” 武漢全民核酸檢測,然後呢?下一步是什麼?[City-wide New Coronavirus Nucleic Acid Test Screening, what is next? What is the next step?], Zhishi fenzi de boke (blog), 19 May, 2020, http://zhishifenzi.blog.caixin.com/archives/228600?cxw=IOS&Sfrom=more&origin Referrer=iOSshare.

- Lu Shan 盧杉, “Guo Guangchang duihua Zhang Wenhong: yao bu yao dui Shanghai 3000 wan renkou zuo hesuan jiance? Haowu biyao” 郭廣昌對話張文宏:要不要對上海3000萬人口做全民核酸檢測?毫無必要 [Guo Guangchang conversing with Zhang Wenhong: City-Wide Nucleic Acid Test Screening for 30 million people in Shanghai? Absolutely unnecessary], 21 Caijing, 15 May, 2o20, https://m.21jingji.com/article/20200515/herald/c39ff7890d58a85e8b79a4ce 65be48af.html.

- Mandy Zuo, “Wuhan wraps up coronavirus tests on 10 million people,” South China Morning Post, June 2, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3087208/wuhan-wrapscoronavirus-tests-10-million-people.

- “Renmin anquan shi guojia anquan de jishi” 人民安全是国家安全的基石 [The safety of the people is the cornerstone of national security], Guangming Daily, June 4, 2020, https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/202006/04/nw.D110000gmrb_20200604_5-01.htm.