Digitalising Death: The Cyberspace is a New Graveyard

Learn about digital graveyards and what it tells about East Asian societies.

Written by Lok Hang Fung

Published on 01/11/2021

As we all will die one day, how to face death and cope with the loss of our loved ones are universal questions. Across different cultures and religious traditions, it is more common than unique to consider the dead as some kind of supernatural beings, to whom we give offerings and talk to, not even knowing whether they can receive or listen. At the very least, we remember them in our hearts, and we hope for the very best for wherever they are going (or we imagine them going).

But mourning today is very different from mourning 30 years ago. In just 30 years’ time, we went from dial-up internet access to broadband to 5G cellular networks. By

2020, over half of the world’s population has internet access.[1] Every aspect of our lives is more or less intertwined with the cyberspace that did not even exist 30 years ago. In fact, not just your life, your death also. The cyberspace has become a new, digital graveyard, where family and friends can remember the deceased through their digital legacies, and where you can decide what and how to be remembered before your own death.

Not a Sci-Fi: Being Remembered Forever, Digitally

Here comes the concepts of digital graveyards and digital grave-sweeping (網路祭祀/ 網上掃墓). There are roughly two types of them: the first and the simplest form is to incorporate technologies in the design of the grave. As early as 1994, we have seen Sugamo Heiwa Reien, a cemetery in Tokyo offering joint tombs where the deceased’s photo and biography appear on a digital screen. In 2020, the technology had a makeover – a cemetery in Chiba, Japan introduced an electronic tombstone equipped with the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) technology. When mourners carrying a special “talisman” go close to the tombstone, the electronic display would automatically show information of the deceased, including names, photos, dates of birth and death, and so on.

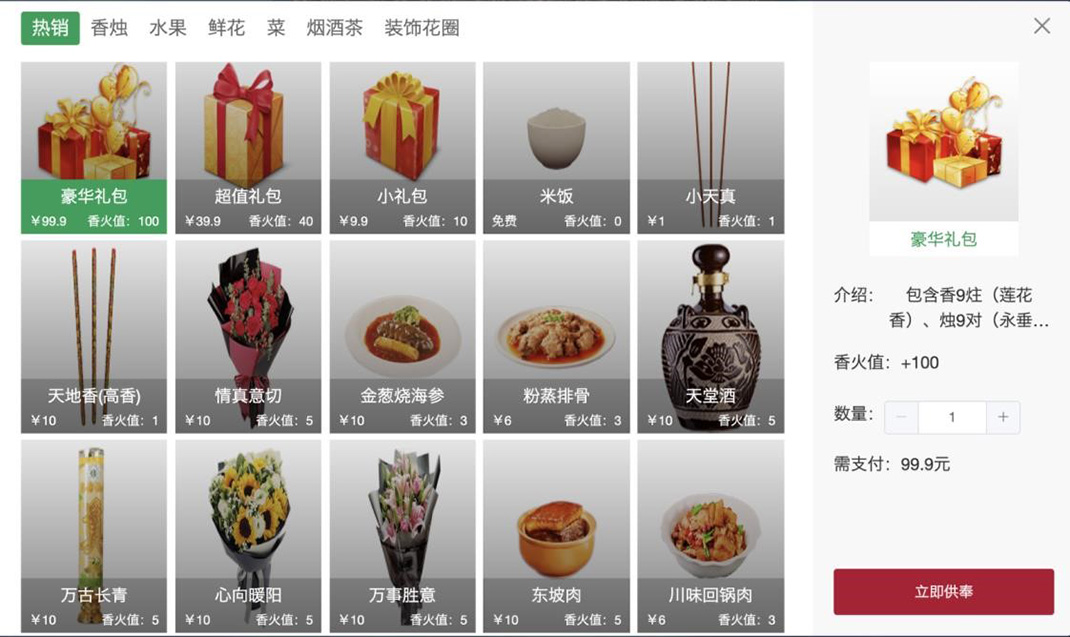

The second type is online memorial websites. An example is “Yahoo Ending” launched by Yahoo Japan in 2014 (service discontinued) which promised to delete all personal data from the company’s online storage, send out farewell emails the deceased had prepared, and set up a digital memorial site where people can leave condolences messages. In mainland China, this kind of memorial website has grown into a huge business: it is estimated that there are over 10,000 online “memorial halls”, mostly paid, some free of charge. Users usually pay a one-off registration plus an annual maintenance fee, and can selectively pay for rituals or offerings. Sugamo Heiwa Reien, the pioneer of digital grave-sweeping we have just talked about, also has a website named Cyber Stone (サイバーストーン), where you can choose photographs, words and even videos and audio to be uploaded before you depart for the next life. Family and friends can “visit” the Cyber Stone anytime and anywhere as long as they have access to the internet. The Sugamo Heiwa Reien has made it crystal clear on their website: “the system is developed to meet the needs of users who have moved far away (from Tokyo) or are too old to visit”.[2] As it hints, digital tombstones and digital grave-sweeping did not just emerge because the internet is too convenient; or because haunty homo sapiens would like more and more control over death. They are, indeed, answers to social transformations. of Cheung. Source: huaien.com. Screenshot by Author.

Japan: Who is Going to Take Care of the Graves?

In Japan, graves are typically family graves (on gravestones, only the patriarch surname is written, e.g. the grave of the ABC family). When a member of a family passes away and is cremated, the ashes of the member would be placed in the same grave as other members of the family. For women, as they typically marry into their husbands’ families, (the Japanese law demands that married couples share the same surname, and data from 2015 shows that 96% of them adopt the husband’s),[3] when they die, they would be buried in their husbands’ family graves. The problem with this system is that ancestral worship relies so heavily on familial structure. Imagine a family with fewer and fewer offspring and just a single daughter in the current generation – who is going to take care of the grave after the daughter gets married (and is technically no longer a member of her natal family)? In Japan and other East Asian societies like South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong where fertility rate is low, population is ageing, and people are marrying late (or not marrying at all), before mankind dies out, the ancestral rituals would be at risk. This is why Japanese cemeteries started to offer digital graves that can be shared by many individuals (so that it is cheaper) and can be visited from afar (to cater for the elderly population). In a society where fewer and fewer people in a family can share the funeral expenses, communal tombs is a much better option (at Sugamo Heiwa Reien, for example, the cheapest communal tomb with digital display costs ¥250,000 while a private graveyard that stores 4 to 12 urns costs ¥2,450,000 plus a ¥20,000 annual maintenance fee). It is also a better choice for unmarried individuals because the cemetery management would carry out rituals in lieu of families and friends.

China: A Long Way Home

In mainland China, there is a different reason why online grave-sweeping sites became a thing. We know how important ancestral veneration is in Chinese folk religious tradition. It is not only Confucian filial piety that urges people to remember their ancestors – the folk religious belief holds that the deceased, as souls, are deified and have a little more spiritual power than us. If they are happy, the family will be blessed (祖先保佑), but if they are not satisfied or have a lack of offerings to use, they might haunt you with dreams asking for something. At least once or twice a year at the Qingming Festival (清明節) or the Double Ninth Festival (重陽節), the whole family should gather together, pay respect to their ancestor, and ask for the ancestors’ blessings and protection (and not haunting dreams). But since the Reform and Opening Up era, a huge number of migrant workers have been displaced (in 2020, there are a striking 285.6 million migrant workers all over China, of which around 170 million have either moved to rather distant places in their home provinces or have relocated to another province).[4] The only times these workers can embark on long journeys home are the Lunar New Year and the National Day holidays. What about the other times of the year or the death anniversary? They need to rely on online virtual grave-sweeping sites. It is a way to compromise being trapped in the capitalist iron cage where humans are treated as work machines, and fulfilling traditional duties that are in fact fading out in modern society.

Dying Green

Another issue is Mother Earth. Ancestral rituals can be very unfriendly to the environment. The smoke from burning incense and paper offerings can be irritative to the eyes, skin and the respiratory system, not to mention being carcinogenic.[5] The burning of offerings is also a common cause of hill fire. Just one day in Qingming Festival 2018, Hong Kong has recorded 97 cases of hill fire, damaging vegetation and natural habitats that take years to be restored. Apart from air pollution and fire, the very act of burning is considered a waste of resources by some. As environmental protection gets more and more attention and as land resources are more scarce, many non-governmental organisations and even governments are promoting the concept of green burial and the toning down of ancestral rituals. A lack of space to house urns and environmental concerns are indeed the Hong Kong government’s number one reasons to promote green burial.

One of the authority’s efforts is to launch the Internet Memorial Service, a website or a mobile app where families can build memorial pages for the deceased in 2011.

The Pandemic

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives tremendously. It feels like all progress of globalisation has been resetted just by a click of a button. Even traditional rituals like grave-sweeping could not safely take place because they entail a huge amount of people commuting and gathering in one location. To prevent this from happening, governments have gone as far as banning ancestral worship at public cemeteries and/or hurriedly launching online remote grave-sweeping platforms. During Qingming 2020, in mainland China, the authorities of Shenzhen, Jiangsu, Liaoning and Jiangsu implemented such measures. In Taiwan also, at least 6 counties or cities have banned citizens from entering columbaria for the same period. The Taiwanese Ministry of the Interior also launched a memorial website and strongly encouraged citizens to stay home and worship online. Nonetheless, however promoted it is, remote digital grave-sweeping is faced with huge scepticism as to whether it tarnishes the true meanings of the rituals, whether it can really replace on-site rituals, or would it actually be a disrespect to ancestors. Even the Minister of Interior himself commented that he “would still go grave-sweeping” because he would feel guilty about not visiting his father and ancestors.[6]

Is There a Limit to Digital “Memory”?

Not just to cater for people who find it difficult to travel back home for rituals, digital graves are going to give people more freedom to decide on how they would like to be remembered after death. We talked about sites where people can curate their own memorial websites prior to death, and in the future, people can actually “live” eternally online. A to-be-launched site Eterni.me has offered to create digital AI avatars that learn your minds and the way you act as you talk to them and/or allow access to your social media, emails and phone. Then 30 or 40 years later, when the “digital alter egos” have learnt enough to actually “become” you, your loved ones can interact with it like you have never left. It seems that humans are so obsessed with fighting against the inevitable that they forget about issues of privacy and obsolescence. How safe is data stored on these memorial websites? Would random netizens or even hackers be able to access information of the deceased? What would happen if our digital alter egos have gone insane? Speaking of obsolescence, as technologies change so rapidly, can the digital legacies we leave behind really be saved and deciphered hundreds of years later, as we optimistically envision? The answers are yet to be known.

Footnotes

- World Bank, “Individuals using the Internet (% of population),” The World Bank Group, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS.

- “O haka nitsuite” お墓について, Sugamo Heiwa Reien すがも平和霊苑, https://www.haka.co.jp/2haka.php.

- Tomohiro Osaki, “Japan’s top court upholds same-name rule for married couples, overturns remarriage moratorium for women,” The Japan Times, December 16, 2015, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/12/16/national/crime-legal/japanstop-court-strikes-rules-divorcee-remarriage/#.VnEKrFIT9r5.

- “Migrant workers and their children,” China Labour Bulletin, May 4, 2021, https://clb.org.hk/content/migrant-workers-and-their-children.

- “The hazards of ghost money”, Taiwan Today, November 5, 2010 https://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?unit=2,23,45&post=1508.

- Wu Chenghan 吳承翰, “Fangyi vs saomu? Hsu Kuo-yung: bu sau duibuqi zuzong, guli fenliu” 防疫 vs 掃墓?徐國勇:不掃對不起祖宗、鼓勵分流 [Disease prevention vs grave-sweeping? Hsu Kuo-yung: “I will be sorry if I don’t go grave-sweeping”, “encourage diversion”], NOWnews, March 9, 2020, https://www.nownews.com/news/3975938.