Faux Meat: Before the Rise of Plant-based Meat

Learn about how Chinese people replicated the taste and appearance of meat with vegetarian ingredients since a thousand years ago.

Written by Lok Hang Fung

Published on 25/11/2021

Introduction

Over the past decade, plant-based meat has become a huge (middle-class) fad around the world due to the growing concern over global warming, the crave for a greener and healthier diet, and the launching of major meat substitute producers, most well-known of all Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. Products of these companies have made their way into supermarkets and multinational fast food chains: the Impossible Whopper, the meatless version of Burger King’s classic.

Whopper is available across North America, Europe, Asia and South Africa; Dunkin’s Donut has, on their United States menu, a Beyond Sausage breakfast sandwich. Just a month ago (October 2021), McDonald’s announced their partnership with Beyond Meat and the U.S. debut of McPlant after trial runs in Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, Austria and the UK. In (usually more high-end) supermarkets in Hong Kong, customers can easily bring home faux meat products like Impossible Beef,[1] Omnipork and related products like plant-based luncheon meat and plant-based pork dumplings. Starting from the United States, the faux meat trend is now sweeping the world as a new middle/upper class lifestyle.

But as vegetarianism has a long history of around 2,500 years that takes roots in various religious practices and dietary concerns, the concept of meat alternatives (meatless food made to replicate the taste, texture and appearance of meat products) has also a much longer story before the rise of Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. As early as year 965 AD, the earliest record of tofu used as meat analogue has already appeared in a book named Qingyilu (清異錄). The author Tao Gu (陶穀) describes how tofu was referred to as “small lamb chop” (小宰羊), which is seen as a proof of the Chinese population consuming tofu as an alternative to meat.[2] In fact, people in China have come up with many ways to satisfy their taste buds and their meaty appetite while practising vegetarianism especially during the time of Tao Gu (Song Dynasty; 10th – 13th centuries), and it has a great deal to do with the practice of Chinese Buddhism.

The spread of Buddhism is probably one of the most important factors contributing to the spread of vegetarian diet in China. Before the entrance of Buddhism from India, vegetarianism in China was considered unusual and practiced mainly during times of mourning. It was only during the fifth century that intervention from the state and the laity paved the way for the normalisation of vegetarianism in Chinese Buddhism by the 10th century.[3] Many attribute the adoption of vegetarianism in Chinese Buddhism to the “Essay for the Renunciation of Meat” (斷酒肉文) composed by Buddha-loving emperor Wu of Liang (梁武帝). A devoted Buddhist, Emperor Wu of Liang eagerly urged Buddhist monks and nuns to adopt vegetarianism by announcing his essay in monastic assemblies he himself summoned. But more important than the Emperor’s petition might actually be the efforts of lay Buddhists who started going meatless because of their obsession with non-monastic karmic stories – lay Buddhists adopting vegetarianism became a pressure for monastic monks and nuns to go for a stricter diet. No matter what, it was clear that by the Tang Dynasty, lay Buddhists had well accepted vegetarianism, and paid quite a lot of effort in making vegetarian dishes as “meat-like” as possible. Here is an example of a lay Buddhist serving fake meat dishes from the book Beimeng suoyan《北夢瑣言》:

唐崔侍中安潛,崇奉釋氏…宴諸司,以麵及蒟蒻之類染作顏色,用像豚肩、羊臑、膾炙之屬,皆逼真也。

(Cui Anqian, a Tang Dynasty Palace Attendant, was Buddhist. When he held a banquet, dishes including coloured noodles and konjac used to mimic roasted pork shoulder and lamb leg were served. They all looked real.)

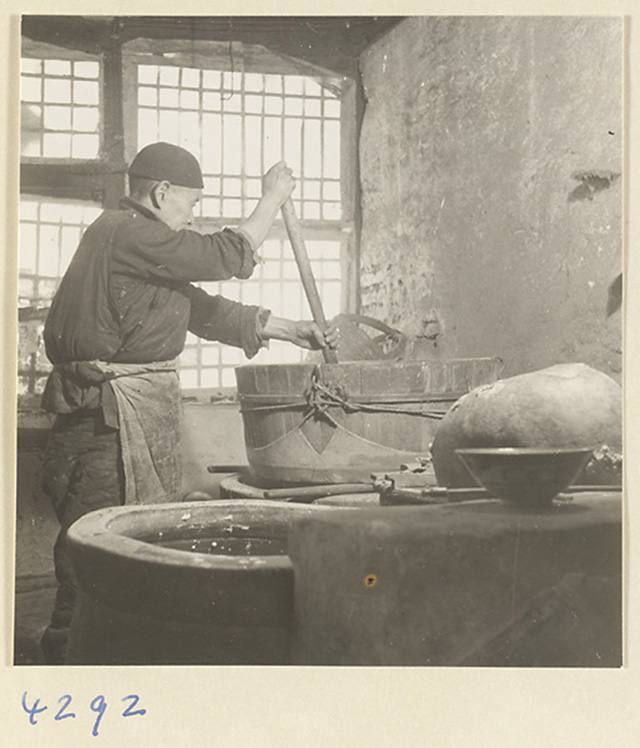

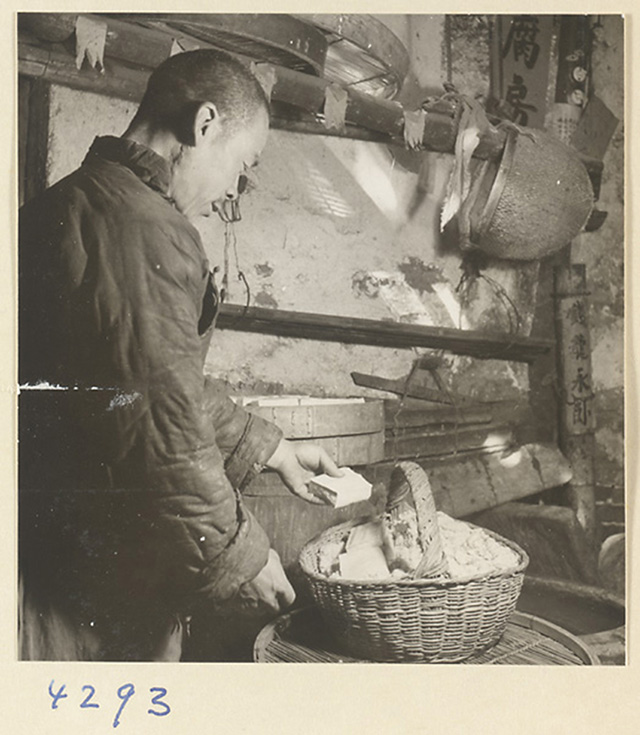

Since the Tang Dynasty (and especially from the Song Dynasty), faux meat (仿葷) cuisine has gradually got a place in the Chinese culinary tradition. The complex faux meat cuisine centres around capturing the flavour, texture and appearance of meat dishes with the use of meat substitutes including wheat gluten (麵筋), mushrooms, and soybean products like bean curd sheet (腐皮) and tofu.[4] But why the Song Dynasty in particular? What is special about this period of time that made the popularisation of vegetarianism possible? There are three possible reasons. First, famous for its economic prosperity and gastronomical delight, markets in the Song Dynasty offered 40 to 50 kinds of vegetables close to what is available today.[5] Cucumber, eggplant, turnip, Chinese celery, cabbage, mushrooms, winter melon and bamboo shoot were all widely available best-sellers. It is only with such a large variety of vegetables can vegetarian cuisine be so well-developed. The second factor is the popularisation of tofu and wheat gluten, the two ingredients that give life to faux meat dishes by mimicking both the textures and appearance of meat, while being a great source of protein. Although both were invented before the Song Dynasty, it was until then were they widely accepted, produced, sold, and loved. Finally, it is likely that the genteel and refined literatis of the Song Dynasty who perceived vegetarian diet as an elegant, posh lifestyle and even a spiritual pursuit have promoted vegetarianism indirectly. Famous writers and poets like Su Shi (蘇軾), Lu You (陸游) and Huang Tingjian (黃庭堅) all expressed their vegetarian hearts in their literary work and thus contributed to the love for vegetarian cuisine.

The Song Dynasty has witnessed a growth of vegetarian eateries both at religious premises and on the streets. At Buddhist temples, mock meat dishes catered for pilgrims, worshippers and people transitioning to vegetarianism; on the streets, there were also vegetarian restaurants (素食分茶) offering all kinds of faux meat dishes.

We are sure that by the Northern Song Dynasty (960 AD-1127 AD), on the streets of the most prosperous capital city Bianliang (汴梁), there were vegetarian restaurants serving dishes “like vegetarian food in Buddhist monasteries” (如寺院齋食也) for lay Buddhists as well as followers of Chinese folk religion. Dishes offered in vegetarian restaurants in the Southern Song period (1127 AD – 1279 AD) were documented in detail, and there was an array of mock meat dishes: fake roast goose, fake pan fried pig intestines with hog maw, pan fried fake black mullet, and fake donkey intestine. Fake donkey intestine (假驢事件) has even made its way to Japan probably through Buddhist monks and the spread of Chinese tea ceremony to Japan. The food is speculated to mimic the cylindrical appearance of intestines, and might have even been the origin of Japan’s “donkey intestine thick soup” (驢腸羹), a steamed dish made of wheat flour, soy flour, arrowroot and sugar served in Buddhist temples as a tea snack.[6]

Today, after a thousand years of development, faux meat has become a common ingredient in vegetarian restaurants across the Sinophone area. Taiwan, one of the most vegetarian places in the world and where over half of the population is Buddhist or adheres to Chinese folk religion,[7] has become the pioneer and centre of meat analogue R&D and production in East Asia. Advancements in food processing technologies have enabled the production of more “meat-like” meat analogues of a larger variety and better quality. For example, the technique of isolating individual compounds from ingredients allowed producers to better mimic the texture of chucks of meat; while the technology of separating protein from soybeans has helped the adding of extra protein content to faux meat products. To keep up with the taste of modern fussy eaters and to make a vegetarian diet as “bearable” as possible, meat analogue producers have also expanded their product range to include non-Chinese food. For example, salmon and tuna sashimi that are very much loved by the people of Taiwan and Hong Kong have their vegetarian siblings.

The more and more meat-like faux meat has indeed sparked the “vegetarian diet but not vegetarian mind” (素口不素心) debate. Some argue that consuming meat analogues entails the desire for meat deep in the heart and should therefore be condemned, while others welcomed the idea because faux meat typically helps transitioning to vegetarianism, and has indeed enriched the spectrum of Chinese vegetarian cuisine. After today, maybe you will have one more perspective to the debate: the reproduction of the texture, appearance and taste of meat with non-meat ingredients has deep roots in the culinary history of China.

Footnotes

- Hong Kong along with Singapore are the very first places outside the United States to have Impossible Beef in supermarkets for retail. The question “why Hong Kong and Singapore” probably has a lot to hint about the target customers of the product.

- William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi, History of Meat Alternatives (965 CE to 2014): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook, (Lafayette: Soyinfo Center, 2014).

- John Kieschnick, “Buddhist Vegetarianism in China,” in Of Tripod and Palate: Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China, ed. Roel Sterckx (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005),186-212.

- Klein, Jakob A. “Buddhist Vegetarian Restaurants and the Changing Meanings of Meat in Urban China.” Ethnos 82, no. 2 (2017): 252-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2015.1084016.

- Zhang Jinhua 張金花, and Wang Maohua 王茂華, “Songdai de shucai yu shucaiye” 宋代的蔬菜與蔬菜業 [The vegetables and vegetable production of the Song Dynasty], Yŏksa munhwa yŏn’gu 33 (2009): 227-248.

- Gao Qian 高啟安, “Zhongguo gudai de ‘lüchang’ yaozhuan – jianlun ‘lüchanggeng’ de bianyi he chuanru Riben” 中國古代的「驢腸」肴饌 ─兼論「驢腸羹」的變異和傳入日本 [“Donkey Rectum” Dish in Ancient China – With the Study of the Variation of “Donkey Rectum Thick Soup” and Its Introduction to Japan], Journal of Chinese Literature of National Cheng Kung University 成大中文學報 34 (2011): 1-20.

- Yang-Chih Fu (2020), 2018 Taiwan Social Change Survey (Round 7, Year 4): Religion (Restricted Access Data) (R090060) [data file]. Available from Survey Research Data Archive, Academia Sinica. doi:10.6141/TW-SRDA-R090060-2.