Rice Cooker: How a Humble Electric Appliance was Born and Changed the World

Written by Lok Hang Fung

Published on 01/11/2021

It is time for dinner. The sweet smell of rice starts to spread around small households in Hong Kong, and the beeping sound from the timer tells that the rice cooker has done its job. The lid is opened. The rice inside the pot looks a bit moist, round and fluffy – not too dry nor too watery. Thanks to rice cookers (Cantonese 電飯煲; Japanese 炊飯器 suihanki), boiling rice, a staple food so central to food cultures all across Asia, has become much easier and faster. Just a little more than 60 years ago, however, cooking rice was a tedious and labour-intensive procedure. Before the time of rice cookers, in Hong Kong, rice was typically cooked in clay pots over portable kerosene stoves (火水爐) or charcoal stoves. In Korea, people boiled rice with Gamasot (가마솥), cauldrons made in cast iron. In Japan, rice was cooked in earthenware and later metal pots on large stoves called kamado (竈) allegedly introduced from Korea (hence the exact same pronunciation “gama”, which is in fact the North Korean term for cooking range).[1] Those who cooked rice (primarily housewives) had to spend long hours paying close attention to the fire and temperature so that the rice would not burn – to make breakfast in time, Japanese housewives had to start sitting in front of the kamado watching and fanning fire at 5am. Rice cookers are revolutionary, for it liberated housewives in places where rice is so important from the hassle of making it a few times a day. And this is only one of the ways how rice cookers are legendary.

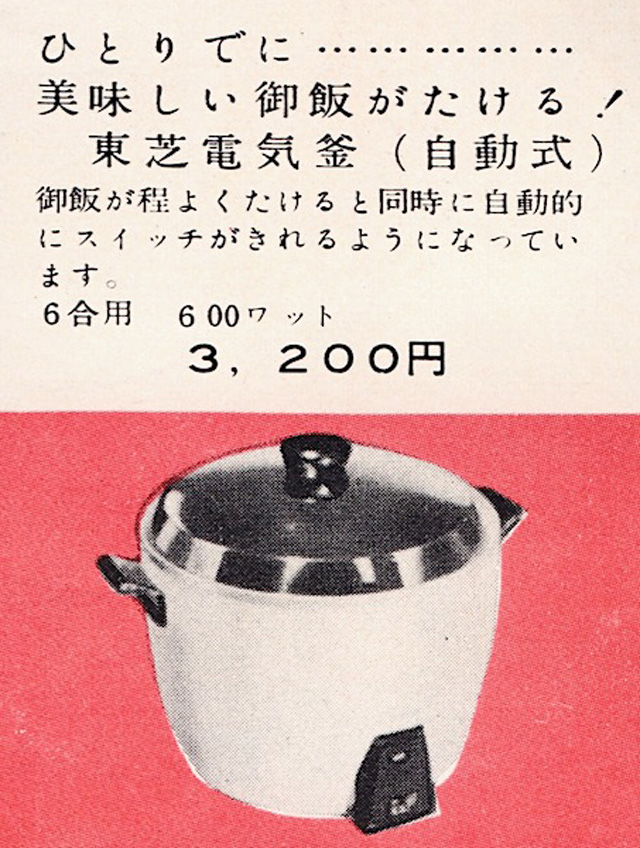

The tale of the rice cooker began in the 1950s, when Japan, where it was invented, was quickly sailing towards recovery after the Second World War. Before that, in the 1920s, there was a simple version of electric rice cooker but it was unpopular because it, like kamado, required full attention from users. Then in the 1950s, Toshiba took on the challenge to revamp the product and develop a fully automated rice cooker. They named the product denki-gama (electric pot) and launched it in 1955, a time when pre-war income levels had just been restored in Japan. The denki-gama was a great success. Housewives around Japan welcomed this invention that saved them much time and sleep, despite it being considerably expensive (priced at ¥3,200, more than one-third of the average monthly income at that time). In just a few years, the Toshiba Er-4 denki-gama has gone beyond the Japanese market and reached the American Japanese population across the ocean. Other companies including Matsushita (now Panasonic) and Hitachi also joined the competition. In 1959, the Matsushita suihanki entered the market. The product name has become the term with which all Japanese people identify this kind of electronic appliance used to cook rice at ease.

The principle behind the technology of rice cooker is straightforward – a heating plate heats up the rice and the water; a thermostat regulates the temperature and switches off heat supply to prevent rice from burning; an outer casing made from aluminium or steel keeps the inner pot warm; and a lid tight enough keeps moisture of the rice. The science is easy, but the details can be unimaginably complicated.

Many experiments were carried out to find answers for the problems like “how long does it take for the rice to be cooked?” “How can temperature be regulated accurately?” and “when should the heat supply be switched off?” What makes things even more difficult is that rice is very different across Asia: the species of rice are different, and people’s standards for “good” rice are different. If the Japanese rice cookers were to be exported overseas, they ought to be changed.

Glocalising Rice Cookers – Adapting to Local Needs and Habits

It was 1960, way before the term “glocalisation” was even invented. The Matsushita team and William Mong (蒙民偉), Japan-born Chinese trader already started revamping Japanese rice cookers to adapt to how Hong Kong people cook and eat rice. Being the one who first introduced rice cookers to the Hong Kong market, Mong insisted that the design of the product must be amended to cater to Hong Kong people’s needs and tastes, and the Matsushita team was determined to meet Mong’s expectations. The end result was historic – the National (樂聲牌) rice cookers sold in Hong Kong have a unique glass viewing pane that allows users to peek inside the pot and know the exact timing to add all sorts of savoury delicacies like Chinese lapchong sausage (臘腸), salted egg (鹹蛋) and salty fish (鹹魚) on the rice. The glass lid also gave skeptical potential customers a chance to see how rice cookers work. Starting from Hong Kong, the gateway to Asia, this model of National rice cooker was welcomed later by Chinese diasporas in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. An undoubted commercial success, the rice cooker made the National brand a household name; and the brand name a symbol of rice cookers. Even when the name National was later replaced by Panasonic, it has been kept solely for rice cookers. On the eshop of William Mong’s Shun Hing Group, we can still find 樂聲牌電飯煲 (National rice cookers), likely because the idea that 樂聲牌 = rice cooker is too deep-rooted in Hong Kong people’s hearts.

Wikimedia Commons, commons.wikimedia.org.

The early localisation attempts paved the way to even greater international sales of National rice cookers. The Matsushita team surely learned a good lesson from cooperating with William Mong who taught them that to cater for local taste and cooking habits is the key to success. Before expanding to a new overseas market, the National rice cooker team would always send staff to visit the locals and hire local taste advisors to ensure an authentic rendition of rice.[2] With this strategy, National rice cookers were able to reach countries where rice is cooked and eaten extremely differently from Japan, for example India and Iran.

Genderising Rice Cooker – the Ones Who Use and Design It

Who is the one who cooks rice in your home? Grandma? Your mom? Or your Filipino domestic helper? Whoever that is, cooking has been a strongly gendered task seen as a woman’s duty in the household. Frankly speaking, I am highly skeptical about whether my father has actually touched our rice cooker even once. He is not necessarily chauvinist, but he certainly has no idea what using and not using the rice cooker implies for the gender dynamics in the house. Therefore, the rice cooker is a conspicuously gendered appliance – mainly used and decided to be purchased by women. The Japanese rice cooker manufacturers knew this very well. Since the early days, manufacturers have targeted young Japanese females through advertisements that featured a cute, feminine tone or chic, well-dressed female models. The introduction of rice cookers along with other electronic appliances, most notably washing machines and refrigerators in Asian households revolutionised the lives of housewives, who can now save some time from routine tasks like going to the market several times a day to buy perishable food; or paying attention to the fire three times a day fearing the rice would burn. Not only are lives a little bit easier, they can also now divert some attention to themselves and to maintaining a “modern”, hassle-free middle-class lifestyle. Some other housewives might even choose to enter paid part-time employment, supplying the much desired labour to the then rapidly growing Japanese manufacturing industry.[3]

The popularisation of rice cookers also created new job opportunities for women. Unsurprisingly, engineers who designed and produced rice cookers (and other female-oriented appliances alike) were predominantly male (although the invention of the first ever Toshiba rice cooker ought to be attributed to the contribution of a woman named Fumiko, wife of a small factory owner). The National rice cooker team did not hire their first female staff until 1979. The female engineers, later known as “rice ladies” in the company, gave the National rice cookers a total appearance and technological makeover. For example, the 1979 model named mai-con denshi jar (in Hong Kong, it is named 西施電飯煲 by William Mong after Xishi, one of the Chinese Four Great Beauties) that is known for its cute, rounded appearance and a handbaglike handle is designed by young female designer for her fellow young Japanese housewives. Another example is the world’s first cake-baking rice cooker launched by National in 2002. This model was developed by a Thai “rice lady” employed by the Matsushita subsidiary in Thailand, where baking was a class privilege because not every Thai family could afford an oven. In a time when engineering was men’s business, the rice ladies proved with their high calibre and unique flair that they are no less than their male counterparts. Still, it would be too optimistic to say that rice cookers would bring any fundamental change to the gender social structure. Indeed, a rice cooker being such a convenient appliance has the risk of reinforcing the conventional gender role.[4] Imagine what the chauvinists might say: “if it is so easy, why should they not do it”?

A Hope for the Modernised Future

Rice cooker was invented when Japan was just a decade into recovery from the war. Electric appliances like the “Three Sacred Treasures” (television, washing machine and refrigerator) and the rice cooker symbolised a better, prosperous future and a modern, comfortable life. In 1950s and 1960s Hong Kong as well, owning these appliances was a huge privilege and a symbol of middle-classness. My mother can still lucidly recall how kids from her neighbourhood all gathered in front of the gate of her flat in a 7-storey resettlement building, because they wanted to peek inside and watch the TV with their envious eyes. As the post-war economy grew, families “below the Lion Rock” moved up the social ladder and worked hard to purchase the appliances one by one, maybe first a refrigerator, then a rice cooker, then a television and finally a washing machine, in the hope and desire of a better future and an easier life. Today, rice cookers have become kitchen essentials in many households around the world. Apart from rice, people have developed with their creativity many recipes to be used in only rice cookers. Cakes, curry, soup? You name it.

Footnotes

- Kim, Kwang-on (Autumn 2017). “A Family Tree: Traditional Kitchens of China, Korea and Japan”. Koreana. 31 (3). https://issuu.com/the_korea_foundation/docs/koreana_20-_20autumn_202017_20_28en

- Nakano, Yoshiko. Where There Are Asians, There Are Rice Cookers. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, HKU, 2009.

- Macnaughtan, Helen (2012) ‘Building up Steam as Consumers: Women, Rice Cookers and the Consumption of Everyday Household Goods in Japan.’ in: Francks, Penelope and Hunter, Janet, (eds.), The Historical Consumer: Consumption and Everyday Life in Japan, 1850-2000. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Matinga, Margaret N., Bigsna Gill, and Tanja Winther. “Rice Cookers, Social Media, and Unruly Women: Disentangling Electricity’s Gendered Implications in Rural Nepal.” [In English]. Original Research. Frontiers in Energy Research 6, no. 140 (January 24 2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2018.00140. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fenrg.2018.00140.