Tracing Apps and Digital Divide (1): Different Technological Designs

In the first article, we introduce the tracing apps in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Singapore as a set of comparative examples.

Written by Jack Linzhou Xing

Published on 29/03/2021

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, tracing apps were developed in various countries and regions in East Asia and the world. Due to different conditions of technological and social infrastructures and social and political traditions, different countries designed and adopted different kinds of tracing apps. In deciding which kinds of technologies or designs should be adopted, convenience to the majority of the people was a central concern. Nevertheless, convenience to minorities, especially socially vulnerable groups, is another important but often ignored concern.

Even without stereotypical overgeneralization, probably everyone agrees that elderly people are generally not as familiar with advanced information and communication technologies as the younger generation. Such a gap of familiarity raises the concern about how to design the tracing apps so that they can be easily used by elderly people. On the one hand, given the widespread and mandatory usage of the tracing app during the pandemic especially in countries like China, the difficulty of usage can directly cause huge trouble to elderly people in their daily life. On the other hand, the difficulty of usage can discourage elderly people to use tracing apps or follow pandemic-control regulations, eventually hurting the effectiveness of the tracing app.

Then, what are the potentially available technological designs of tracing apps? Are they easy enough to use in the eyes of elderly people? Why and why not are certain technological designs adopted, and do these decisions of adoption concern the convenience of elderly people? If not, why, and how do we move forward? This series of articles aims to provide some insights into these problems.

In the first article, we introduce the tracing apps in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Singapore as a set of comparative examples.

Create an App or Build into an Existing System: A Big DifHealth QR Code in China: Centralized Data-saving and GPS Trackingference

The Chinese version of the tracing app, or mini-program (xiao chengxu, 小程序), is called out “Health QR Code”. As the name suggests, it is a program, or a subfunction, built into an existing app – WeChat or Alipay. Before the user applies for a Health QR Code, he or she needs to first have a WeChat and Alipay account, which nowadays requires some information about his or her identity, such as the ID number and his or her real name. When a user applies for a Health QR code, he or she needs to open WeChat or Alipay, go into the mini-program interface, fill in an electronic form containing many questions about personal profiles, living addresses, and recent travel histories. All the information will be transferred to the data center of the local government. The data center will then assign a Health QR Code to the user. Moreover, based on the information filled in, including but not limited to whether the user lives in or has recently traveled to cities or districts with infected cases, the data center will also assign an initial color to the Health QR Code for the user. Specifically, the red code indicates that the user comes from a high-risk region, is subject to a 14-day quarantine, and should be denied from entering any public spaces. The yellow code indicates that the user comes from a medium-risk region and is subject to 7-day quarantine. The green code indicates that the user comes from a low-risk region, has a low possibility of having contact with potential infected cases, and can go into public places freely.

The Health QR Code can be used in two ways. First, when entering public places, the user needs to open the WeChat or Alipay app, go into the mini-program, and show the color of the Health QR code for entry. Second, in public places with interface machines connected to the data center of the local government, such as hospitals, the user can scan his or her Health QR code and show his or her detailed profile and travel history to the staff. In this sense, the color of the code is more of an indicator that enables quick judgments. The information that really matters is the personal profile and travel history.

Moreover, it is noted that users are required to always turn on the GPS function of their smartphones, because the WeChat or Alipay groups use the GPS function to monitor and record the travel track of the user, and transfer the data directly to the local government data center. Therefore, when the user recently traveled to, say, a high-risk region, the color and information saved in the Health QR code will directly be updated.

Even before discussing the implication of such a technological design to elderly users, the Health QR Code was often criticized because of its lack of protection of users’ privacy. The fact that all the data, shared by Alipay or WeChat with the local governments, are automatically accessible to the governments all the time, makes every piece of information about users’ IDs, real names, photos, profiles, and travel histories subject to exposure.

LeaveHomeSafe in Hong Kong: Tracing by Fixed QR Codes

In comparison, the Hong Kong version of the tracing app, LeaveHomeSafe (安心出行), adopts a different strategy which uses fixed nodes of registrations – QR codes of public spaces – to trace the mobile circulation of people.

LeaveHomeSafe is an independent app developed by the government. For the sake of convenience and privacy, only a phone number is needed to register to the app. Different from the Health QR Code program which automatically monitors users’ travel history, LeaveHomeSafe requires users themselves to record their travel history: each public space (restaurants, movie theatres, shops, etc.) are regulated by the government to apply for a unique QR code and stick the code on their gates. When a user comes into the place, he or she is required to screen the QR code by the app. When leaving the place, he or she should click “leave” in the app. In case the user forgets to click “leave”, the app will automatically change the status to “leave” in four hours after the initial scanning of the QR code. In the settings of the app, the time limitation of the automatic leaving function can be adjusted by users.[1]

Another difference between LeaveHomeSafe and Health QR Code is that the data for the former app is only saved within the users’ smartphone rather than in a data center managed by the government. Especially in dealing with the public distrust of the government after the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Movement, the government tries to address the public concerns over privacy by claiming that only when an infected case appeared in a certain site would the government access the phone numbers of the users who screened the QR code for the same place at a similar time.

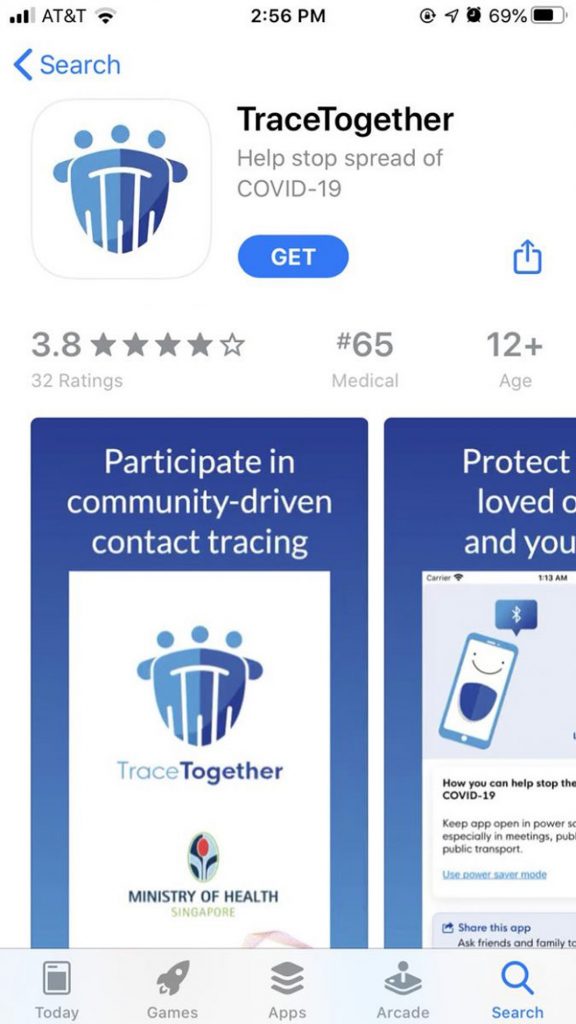

TraceTogether in Singapore: Tracing via Bluetooth

The Singaporean app, TraceTogether, developed by the Singaporean government, is based on a completely different technology – Bluetooth. It is also an independent app. Taking advantage of the feature of Bluetooth that the connections between devices can only be established when the distance between devices is short enough, the app records the TraceTogether accounts of phones that are connected with it.[2]

One advantage of the Bluetooth technology is its easiness of application. As long as the app is downloaded to the smartphone, and the Bluetooth function is turned on, the app functions without any additional operation. Besides the smartphone app, the Singaporean government launches the TraceTogether Token, which is a small Bluetooth device designed for users who are not willing to or do not know how to use the smartphone app. This makes the system even more accessible.

Similar to the Hong Kong government, the Singaporean government also claimed that it will only assess the records of the TraceTogether devices owned by infected users or close contact users, so as to protect the privacy of users. Actually, one of the reasons why the Singaporean government adopted the Bluetooth technology lies in its better protection of privacy based on its peer-to-peer connection nature, which does not require any centralized agents to manage the contact data.[3]

Footnotes

- LeaveHomeSafe. 2020. “LeaveHomeSafe.” Accessed Mar 29, 2021: https://www.leavehomesafe.gov.hk/sc/.

- Stevens, Hallam, and Monamie Bhadra Haines. 2020. “Tracetogether: pandemic response, democracy, and technology.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 14, no. 3: 523-532.

- TraceTogether. 2020. “TraceTogether.” Access Mar 29, 2021: https://www.tracetogether.gov.sg/common/token/